A manifesto for architecture education in the 21st century

The values embodied within 19th and 20th century models of architecture do not completely address the problems of the 21st century. The value system embodied in architecture education and the profession needs to be recalibrated to meet the challenges of the future. This manifesto makes 35 statements advocating for architecture that is inclusive, democratic, equitable, humane, sustainable, innovative and creative. This manifesto is a call to action.

From 19th and 20th century models to a 21st century model

From architecture as buildings

To architecture as the designed and built environment.

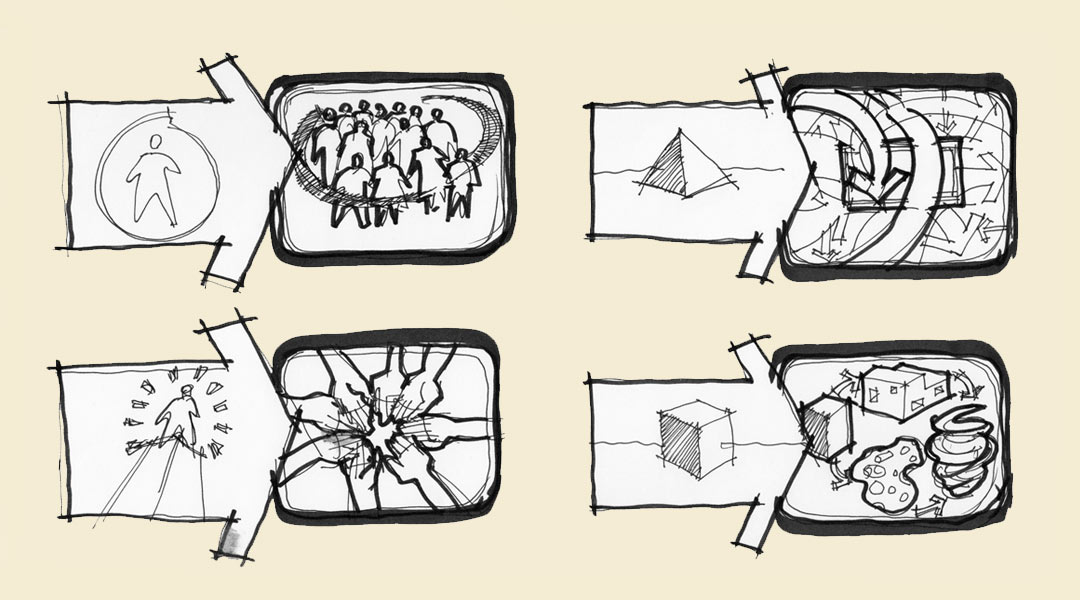

From architect as singular author

To architect as multiple authors.

From architecture as homogenous voice

To architecture as heterogeneous voices.

From architect as preeminent project leader and professional

To architect as collaborator, conduit, facilitator, and team member.

From architecture as isolated profession

To architecture as collaboration across disciplines and networks.

From architecture as singular and specialized profession

To architecture as diverse, multifaceted and multi-disciplinary.

Architects should go beyond thinking of the architectural object as the ultimate goal, and consider the processes that engender the designed environment. Architecture is a system, rather than an isolated object. We must teach our students to learn from a wide array of disciplines and fields, such as neuroscience, anthropology, engineering, medicine, art history, philosophy, and others. Schools should make students work in interdisciplinary teams. Instead of focusing on buildings, projects can revolve around larger issues or themes, such as water, mobility and resiliency—topics that encompass broader and more complex concerns. This process requires multiple disciplines all working together to solve urgent and intricate issues. Teachers should help students to simultaneously ground their work on the designed environment with learning and insights from other fields.

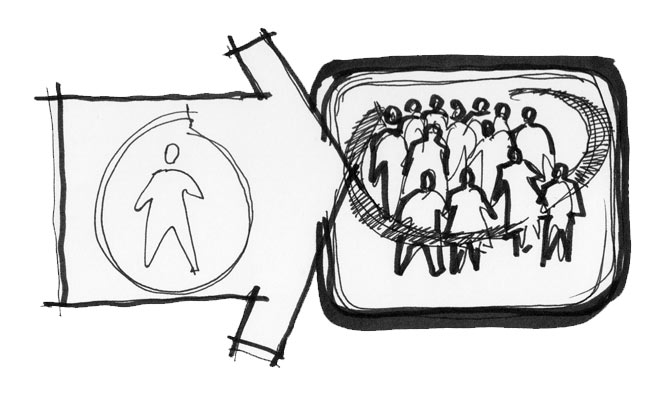

From architecture as grand gestures

To architecture as small and incremental.

From architecture as elitist

To architecture as populist, participatory and democratic.

From architecture as designed only by architects

To architecture designed by everybody.

From architecture as top-down and autocratic

To architecture as bottom-up and participatory.

From architecture for the privileged few

To architecture for the common good.

From architecture as cool objects

To architecture as human-centered design.

From architecture as proprietary and specialized body of knowledge

To architecture as open-sourced and shared body of knowledge.

Architecture focuses too much on people with money and power. Whereas the histories of architecture emphasize monuments and mega-structures as the epitome of great architecture, teachers should cover a broader scope of the designed environment. History and theory courses should discuss efforts of ordinary people in shaping their environments. Architecture history needs to be rewritten to include those who are voiceless and have been rendered invisible.

In teaching studios, we must include users who may not have the capacity to pay for our services. Students need to learn to design for everybody. Schools should teach participatory design processes that engage with the community. Projects should include small and everyday scenarios. Teachers: Architecture should not strive only to be iconic.

Students should be trained to listen. Schools should teach architecture as participatory design—design emerging from the users. In a human-centered approach, teachers will need to learn diverse skills such as interviewing, ethnography, participatory observation, artifact analysis, discourse analysis, qualitative and quantitative analysis, and other tools so that they can teach these in turn to their students to enable them to deeply understand their users. Teachers, remind your students that they are not to impose their own values but to serve as channels of their users’ needs and hopes.

READ MORE: WAF has a student competition that the PH already won

From architects serving only 10% of the population

To architects serving 100% of the population.

From architecture biased towards white, heterosexual and able-bodied males

To architecture for all, regardless of gender, race, class, sexuality and abilities.

From architecture as wasteful and shortsighted

To architecture as sustainable and future-oriented.

From architecture as individual expression

To architecture as expression of multiple perspectives.

From architecture as isolated and autonomous form-making

To architecture as a complex system of economic, political, socio-cultural and ecological imperatives.

Architecture should be inclusive. Projects should address the needs people of diverse backgrounds, abilities, contexts, and types. Schools must teach students universal design principles, and to apply them in various scenarios.

Architecture history needs to be rewritten to include those who are voiceless and have been rendered invisible.

Architectural education should embody sustainability in every phase of design. Sustainable design should engage the ecological, economic and socio-cultural dimensions of the environment. Following systems theory, architecture is understood as part of an interconnected system. Our next generations of architects need to learn to design within this complex system.

In conjunction with sustainability, schools must teach future scenario planning methods, where students are taught to not just think of the present situation but also anticipate possible future conditions. Teachers, show your pupils how to identify larger trends and drivers that shape architecture, and have them design accordingly.

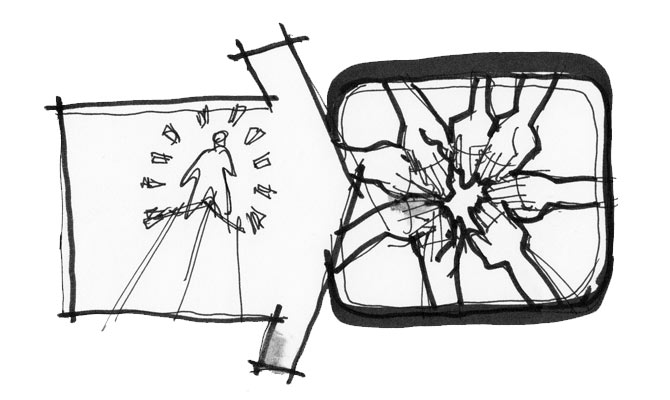

From architecture as beautiful, simple, and pristine object

To architecture as polyvalent, messy and complex.

From architecture as commodity and object

To architecture as process and product.

From architecture as produced, sold and consumed

To architecture as created, experienced and shared.

From architecture as static

To architecture as dynamic.

From architecture as fixed, immutable and permanent

To architecture as agile and adaptive, and ephemeral.

From architecture as defiant

To architecture as resilient.

While aesthetic qualities and formal manipulation have been emphasized in the past, architecture education in the future should not simply focus on architecture as a final object. Students should understand the entire process of creating architecture from conceptualization, to construction, to its being used. Schools should teach design as an iterative process where learning from failure often enough allows students to refine their ideas.

Next, students also need to understand the complexity of the built environment by being exposed to building processes. Prototyping would be an integral step in actualizing ideas. Schools should integrate within their curriculum design-build programs where students are allowed to experiment their ideas through actual construction, to expose them to the intricacies of building and the material conditions within which they are designing.

After the design is implemented, students also need to see and understand how users have adapted to the building, and how the environment has changed the building. Teach students post-occupancy evaluation methods so they may assess the life of buildings after they have been turned over to users. Students need to learn to design architecture that is resilient to changes within and outside architecture. Through a cycle of conceptualizing-iterating-prototyping-refining, the design process recognizes architecture as always in a state of flux.

From architecture as sculptural objects in the landscape

To architecture as immersive experience.

From architecture as self-referential form-making

To architecture as design thinking and problem solving.

From architecture as blind appropriation

To architecture as critical thinking.

From architecture as uncritical following of rules

To architecture as creative, inspiring and imaginative.

From architecture as artistic expressions only

To architecture as entrepreneurial and innovative.

While architecture has been rooted in materials and structures, it should not be reified into merely a type of form-manipulation where the ultimate goal is to create a unique form. Students need to see their form making as part of a larger process of innovation. Architecture education should foster innovation, critical thinking and entrepreneurship as core values. We need to teach them how to innovate by learning from the sciences and the humanities. Critical thinking should be integrated in the curriculum so that students may begin to question, challenge and innovate.

Too many students—and architects—think they will change the world merely by dropping their icons and monuments on the land.

Highlight creativity in the curriculum to encourage students to develop a sense of exploration and curiosity. Imagination should be at the core of the design process. While recognizing that design has its limitations, it should not hinder the imagination of future possibilities. Rules, codes and laws are necessary guideposts in designing, but these should not straight-jacket a student’s creativity. Additionally, optimism should also be fostered. A sense of hope and positive thinking should be practiced throughout the learning process.

Include lessons on phenomenology. Architecture is about experience. Teach students not just to design objects, but most importantly experiences. Put the needs of the users at the forefront, and architecture becomes the creation of positive and ennobling experiences for these people.

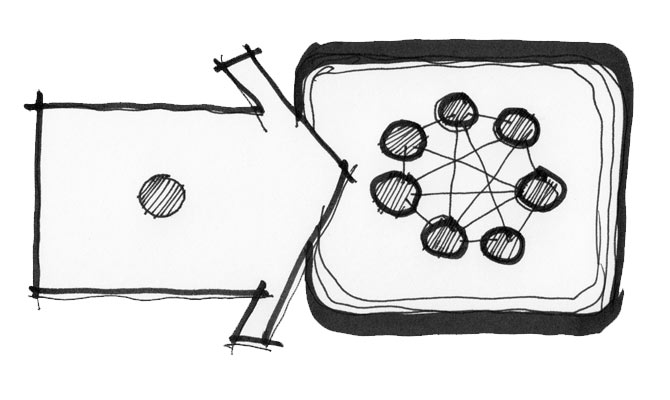

From architecture as passive objects

To architecture as catalyst of change.

From architecture as apolitical and amoral

To architecture as social justice and equity.

From architects as passive by-standers

To architects as active agents of change.

From architecture as apathetic

To architecture as empathetic.

From architecture as firmness, commodity and delight

To architecture as empowering, experiential and ennobling.

From architecture as oppressive and subjugating

To architecture as liberating and emancipating.

Too many students—and architects—think they will change the world merely by dropping their icons and monuments on the land. We often teach architecture as passive, innocent, neutral and inert objects. Instead, we should teach that architecture has the capacity to instigate change in the world. Students should be trained to become as activists advocating social causes and mobilizing the community. The world needs social entrepreneurs, able to address social problems with an entrepreneurial approach and innovation. Change is necessary and designers should become catalysts of such change.

Architects need to learn how to be empathetic. Traveling should be part of the courses. We must immerse our students in different living conditions, work situations and social settings, including areas of intense poverty and humanitarian concern to understand what people truly need. Students should be required to perform community work as well. Students can design and build projects for the community, focusing on urgent needs and issues.

Schools should be advocates of social justice. Lessons must include learning about global issues that affect people, such as poverty, inequality, global trade, modern day slavery, environmental degradation, and others. The study of history as well as current events should be integrated in the courses. Students need to engage in community activities, not just as innocent by-standers but as active participants in social change.

I see pockets of genuine change taking place in architecture education. In general, schools make an effort to impart values, which, when taken to heart, will help direct our future professionals towards paths that contribute to society and the world in general. However, too much of our teaching is lipservice, and too much is left in the realm of theory. We have been way too complacent and lazy to think and change. We also cannot let money and power drive how we teach, learn and, ultimately, how we live. We need our students to get their hands dirty, to dig deep, to see from multiple perspectives.

For genuine change to occur in architecture education and architecture, we all need to work together—schools, students, teachers, administrators, professional organizations, institutions, users and clients. Architecture that empowers and emancipates people, and instigates positive change in the future is not something that will happen by chance. We cannot leave the betterment of our world to chance. The future lies in all of our hands. We need to change now. ![]()