CAZA relates earth and sky in the Home of Many Moons

Binoculars hang from her neck. She looks up to the heavens. Her conscience explodes with visions of celestial bodies falling in the garden. She walks, quietly tending to each plant, smelling the herbs and cutting a few vegetables for her next meal. She is a lady of the stars and of the earth.

With these poetic words, Carlos Arnaiz introduces his project, A Home of Many Moons. It is shortlisted at the 2015 World Architecture Festival (WAF), in the Future Projects, House Category. Three other Filipino architects are shortlisted as well, and we are at an intimate gathering of architects organized by BluPrint and Grohe to celebrate their success. The event is like a dress rehearsal for the WAF, with the four presenting their projects to the small crowd.

Arnaiz is up first, and my hope for him to win is reinforced as I listen to his narration. Not just for Filipino pride, but because Arnaiz for me is an anti-Roark. That outdated Ayn Rand novel, The Fountainhead, which romanticizes ego and individualism, still exerts undue influence today.

Too many moody young architects fancy themselves as Howard Roark—brilliant, ahead of his time, and uncompromising. All his buildings are the embodiment of himself—long, hard, lean, strong, angular and arrogant—including the house he designs for his lover (and client’s wife). For inexplicable (somewhat perverse) reasons, the woman welcomes Roark’s act of domination and control over her. When she moves into the house, she thinks: “I belong to him here as I’ve never belonged to him.”

READ MORE: Furunes + Locsin’s Streetlight Tagpuro qualifies for WAF Building of the Year

In contrast, while one might fancy a lover’s tone in Arnaiz’s dreamy description of his design for the “lady of the stars and of the earth,” one gets no sense of him imposing his ego on the project, nor his will on her. If young Modernists must idolize someone, then let it be Arnaiz, a man of fluent forms, and stirring speech, but whose earnest positivity, attentive and thoughtful mien make him nothing like the contemptuous Roark.

This is a home for her. We knew it had to be part ground, part sky. It could not dominate its surroundings with Modernist certainty. This is a home with two ways of seeing. It looks out timidly with a slanted horizon and gazes upwards with eyelids clipped by the phases of the moon. Its geometry comes from a marriage of these two kinds of spaces. They tunnel down and project up. Intersections are the areas of solidity. The home appears to be excavated from alien monoliths. The house is built on an understanding that dualities are inevitable.

When Arnaiz talks of dualities, he can empathize. Born of a Filipino father and Colombian mother, he was educated in Manila and then in New York. He double-majored in Philosophy and Literature before taking his master’s in Architecture and now practices out of offices in three different continents.

The Home of Many Moons, Arnaiz modestly confesses, could not have been conceived without the “bizarre and fascinating” brief of the client. “She wanted a house that was very private, very austere, very monastic, while at the same time very connected to the landscape,” Arnaiz recounts. The brief proposed a contradiction, Arnaiz relates. “The house wanted to be closed and inward looking; but at the same time the garden and surrounding area, which are much larger than the house, had to be very much part of the house.”

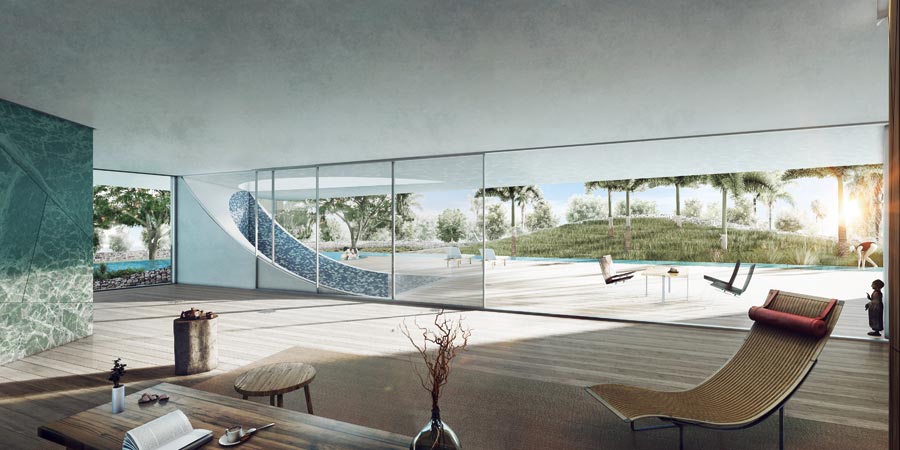

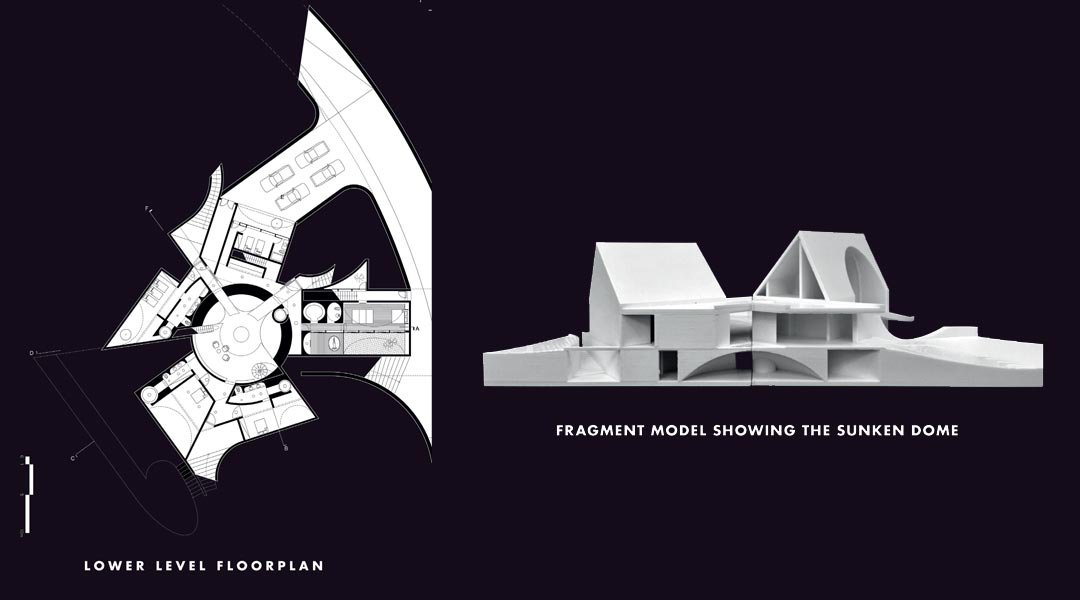

And so the inside outside relationship became the main design concept, and the big idea that emerged was House as Device to relate to the sky and earth. The initial concept diagrams show the house functioning as both terrascope and telescope, framing horizontal panoramic vistas and scenes of the sky.

Our first view is a pair of stone homes rendered in elemental purity as pitched volumes in the landscape. As we approach, the stone walls and garden paths open out like the tentacles of a giant squid angling its body towards the sky. Built into the ground with surgical precision, the house is a kind of somnambulist apparition: enigmatic in its combination of unfamiliar forms and assaulting us with the veracity of hand-made materials such as stone, poured-in-place concrete, and glazed ceramics.

The two stone structures are not so alien to Filipinos; they have the look of the indigenous Ivatan houses of Batanes. Viewed from the bamboo thicket of the property, the use of stone and the archetypal form make them appear ancient and ageless. Thanks to one large opening on the otherwise solid façades, the inscrutable feels knowable.

The plan is a pentagon, and every room is one side of the pentagon. Every room looks out with a horizontal way of seeing to one side of the one-hectare grounds. The bedrooms, on the other hand, are each cloistered in a courtyard; and one’s only contact with the outside world is to look up at the sky through an oculus or a skylight in some shape of the moon.

“Who is this client? Tell us more about her!” several members of the audience ask Arnaiz when he is done presenting his concept. They are convinced that the design is in response to this Lady of the Stars and of the Earth, and not mere whim. To know her is to understand his inspiration and the design decisions Arnaiz has made. He declines to share personal information, however, and reveals only that she is single, and the idiosyncratic rumpus room in the basement is for visiting young relatives.

This home prescribes a paradigm that resists simple singularities. It is based on the idea of the crossbreed. The top floor clusters inwards then extends out. The bottom floor tunnels downwards then bulges up. The solid parts are peeled open, revealing soft surfaces while the interiors consist of an open pentagon framed by marble parallelograms.

What the Home of Many Moons and its architect have in common is resistance to simple singularities. Arnaiz avers that he observes no particular style and favors no single aesthetic. He pays obeisance to no dogma, and will not espouse Modernist, progressive or “transformative” agendas either.

“We don’t have an answer to everything,” he says. “My style is just to ask questions. Every project is a new inquiry; a new quest to discover what can be unique to it. To have a style is to shackle or straightjacket the possibilities of a project.” Instead, his approach to projects is the Socratic method— continually asking probing questions to illumine ideas and quicken critical thinking.

“One of the aspirations I have for projects is I don’t want them to look like anything I’ve ever seen. If it looks like a Modern house or something that I’ve seen in magazines, then I’ve already lost the game,” he confesses.

Producing something new under the sun is too shallow a motivation for Arnaiz, however. While a junior at Williams College where he graduated magna cum laude, he took a Literature class called Space, Place and Fiction, which would influence the direction of his life. The class would read and analyze novels where the setting is critical to the development of the plot. This made him ponder deeply about how environments impact people, and indeed, shape the development of our lives’ plots. It wasn’t long before he made the jump from Philosophy and Literature to Architecture at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design, where he graduated with honors.

Each room of the home connects the traditional idea of domesticity with a specific way of relating to our environment. Like her, the home is comfortable with dualities: a devotion to the horizontality of the landscape and an insistence to look up towards the stars. She walks through her home both present and detached, measuring herself against this new earth.

Arnaiz has answered the questions in the time allotted for him—the same length of time the WAF gives its finalists. He leaves the audience both satisfied and wanting more. There is a sense of relief that he knows what he is talking about and will do well at the WAF. I also get a sense of anticipation of great things to come.

The Home of Many Moons has begun construction. How will this singular setting with its dual ways of seeing impact the owner’s life? We may never know, as the Lady of the Stars and of the Earth insists on her anonymity. I hope it marks a significant moment in the trajectory of Philippine architecture. Then maybe there will be less moody railing against iniquities and stupidities in our self satisfied architectural blogosphere.

May there instead be more of the earnest positivity and probing inquisitiveness of Arnaiz. Private spaces like master bedroom have their private gardens. In these sequestered spaces, one connects with the outside world by looking up at the sky. ![]()

The World Architecture Festival 2015 took place on November 4-6 at the Marina Bay Sands in Singapore. Grohe is a founding sponsor of the WAF. BluPrint thanks Grohe Philippines for supporting the four Filipino shortlisted architects, and for making this feature possible.

This article first appeared in BluPrint Special Issue 3 2015. Edits were made for BluPrint online.