Tropical Mid-Century Ranch: House Number 17

Nestled in the rain-drenched slopes of Camiguin’s Mount Hibok-Hibok is a tropical version of the Mid-Century Ranch House beloved of architects and the middle-class of the 1950s. The house is angular but relaxed, and evocative of the sleek, comfortable, and enjoyable airiness suffused with the clean lines of the International Style of the late Thirties, like those built by the great Austrian-American architect Richard Neutra (1892-1970) in the valleys and canyons of Southern California. Los Angeles Modernism was thus the inspiration behind House Number 17 in Camiguin designed by Edwin Uy, whose use of abstract geometry does not come at the cost of livability and environmental sensibility.

Perhaps inspired by Neutra’s sensitive use of cubistic lines and structural organization that he derived by comprehensively interviewing and “profiling” his clients’ needs, Uy has managed to integrate his Mid-Century modern design both to tailor to the client’s specifications of a retreat-style house with wide verandahs facing the sea below; as well as an environmental sensitivity to the site, which is on the slope of a dormant volcano, strewn with ancient volcanic boulders, and blessed with a thick canopy of trees.

It is the tranquility and abundance of nature that first drew the client to this 2,820 square meter lot. A former LA-based realtor and scuba diver, the client fell in love with the site, and believed in Uy’s vision of a house that felt like a resort, but is still a very private residence. The client finalized the site plan with Edwin in mid-2013, and House 17 was then constructed between September 2013 and December 2014.

“House Number 17 was designed to respect the existing terrain and landscape,” Uy relates, “and we did as much as we can to retain the natural boulders of the site. We also used the volcanic rocks on-site to create the facing materials you can see in the house, except for the concrete floors, which are finished with Sika EpoCem, which gives a highly polished white marbled effect to contrast the browns of the local stone.”

House 17 is approached via a sloping driveway, whose view of the main façade is punctuated by broad panels of volcanic stone-dressed walls forming a rhythmic pillar motif, allowing the house interior to peek through sleek rectangular fenestration framed by rectilinear lintels. Although the driveway is also faced in cut volcanic cobblestones, the façade panels are contrasted with smoothly polished volcanic stone embedding, which creates a lush contrast of textures. This is contrasted in texture by rust-brown mahogany timbers from nearby Bukidnon, which Edward uses as cladding in one of the entrance pylons, as well as the house’s rear façade. This creates an overall yin-yang effect between stone and wood external finish, both subscribing to local materials and workmanship, and recalling another Mid-Century theme, the tsalet/bungalow timber and “crazy-cut” cladding of the late-Forties to Sixties.

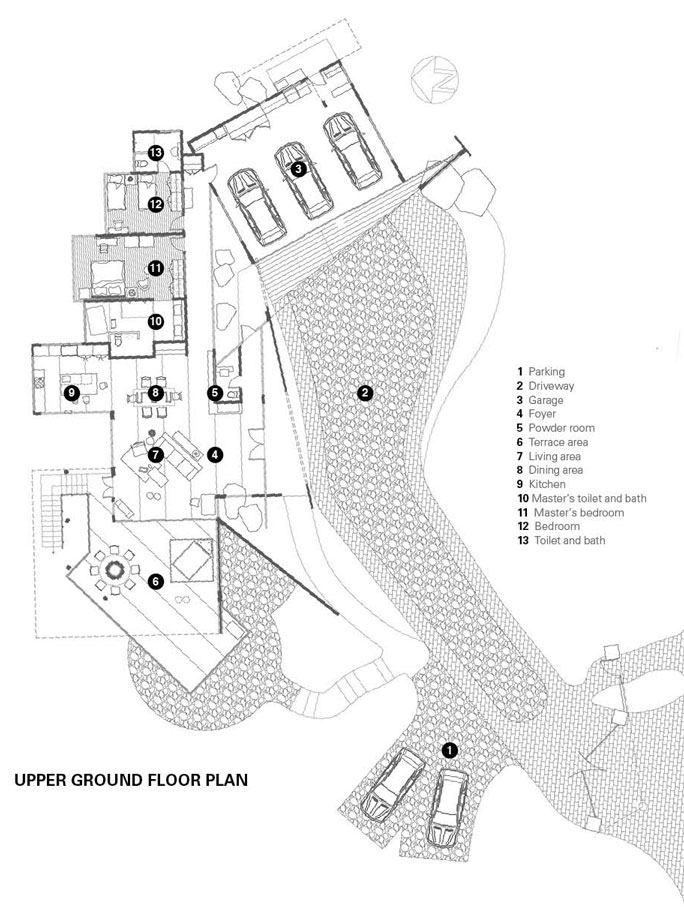

Oriented towards the north-south axis that directs the sea breezes into and out of the structure, House 17 sits on an elevated platform that slopes down towards the sea on its west side, opposite to the east-facing driveway. Its horizontal mass is therefore anchored against this slope, which abuts to one side that creates space for a basement level gym and wine cellar to its west end. On the main level can be found the living room, dining room-kitchen wing to one axis; and the two bedrooms with toilet/baths, and powder room on the opposite axis, which bends in a tangent to join with the garage, its transition spaced by a bamboo mini-garden that one can see from the powder room. Totaling only 340 square meters for the living room-dining room wing as well as the bedroom wing, another 110 square meters were then added to create a large, airy verandah where house users can lounge facing the sea, and from where they can descend into the basement level.

Being environmentally sensitive meant that House Number 17 had to be naturally ventilated (the client insisted on not using air-conditioning except for the bedrooms). Edwin’s design solution was to create floor-to-ceiling fenestration using Mid-Century style glass jalousie windows that faced the sea breeze as well as the mountainside breeze, creating natural cross-ventilation on the inside. It also meant that the north-south orientation of the house was crucial in catching the breezes that blows in from the bedroom wing to the east; as well as the living room/kitchen wing to the west. Remarkably, the house uses electricity exclusively from its roof solar panels, and is completely off-grid sufficient, its solar batteries stored in banks at the garage. Water is also no problem, thanks to the mountain’s copious rainfall that is stored in filtered water tanks, and is so clean that you can drink it straight off the tap. Sensibly, the house also uses mostly LED bulbs and inverter appliances that keep power consumption low and maintenance-free for several years. A light tunnel in the basement also helps illuminate the gym and pedestrian walk underneath from the east side, while the pilotis-style pillars to the west side help catch the wind breeze and light for the verandah and gym. Wide roof eaves help keep rain from entering the house, and are framed in concrete box slabs to retain the clean lines all the way to the top side of the house.

This environmental conservation sensibility extends to interior and detail accents as well. Edward retained several large boulders in the foyer area, and had the threshold custom-fit with a glass wall, providing a visual continuity between the outside and inside, and maintaining a “dialogue” with the primeval character of the site. A rug from nanimarquina titled Global Warming also exerts a compelling conversation on the environment in the living room, while a Jay Pacena painting evokes the multiplicity of Filipino identities that throbs warmly in this cool Mid-Century interior. House 17 is thus a stunning achievement of environmentally sensitive design, and evocation of Mid-Century Pinoy Modernity that the young Edwin Uy has wrought from the classic ranch house set on Camiguin’s misty slopes, a terrain and design solution not different from Richard Neutra’s 1929 masterpiece, the Philip Lovell House. ![]()