Jorge Yulo’s Mecha Uma draws praise from INSIDE judges

“Fantastic,” says Michael Goodman, chair of the three-man jury panel. Jorge Yulo has just finished his presentation of Mecha Uma, one of six interior design projects shortlisted in the Restaurant and Bar category of INSIDE World Festival of Interiors, a global interior design competition, and sister event to the World Architecture Festival 2015.

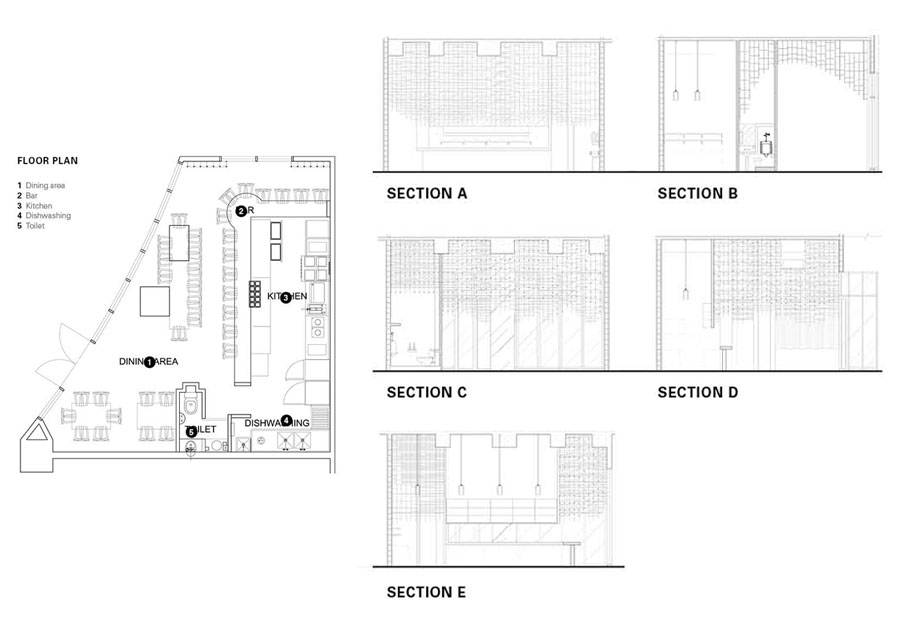

Yulo, the last finalist in his category to present, waits quietly for the judges to throw the first question. They are smiling and seem to be savoring his simple but striking concept for the small, 65-square-meter restaurant. The smiles must count for something, I think, because they sure weren’t smiling during the crits I attended earlier in the day.

Mecha Uma design concept

Flashback nine minutes earlier: Yulo begins his presentation by describing the restaurant as a chef-driven destination at Bonifacio Global City: “Mecha Uma centers around a young chef who has had no formal culinary education. All concerns about his uncertain qualifications to serve Japanese food are appeased when his food explodes on your palate.” The chef is emerging talent Bruce Ricketts, and his approach to cooking is called, “ingredient interpretation”—he works with what he finds at the market and lets that shape what and how he cooks for the day.

“Mecha Uma is the young chef’s culinary performance venue. How do I capture that architecturally or visually? And what will be my narrative?”

READ MORE: Genius Loci: Hacienda Community House by Jorge Yulo

Yulo then describes how human visual perception works—how our eyes don’t actually see images but lines and motion, and how, until our brain recognizes them, the images sent to our brain are fuzzy patterns. “I used this manner of abstraction for what I imagine is going on in the young chef’s mind when concocting a new dish.”

Yulo shows examples of fuzziness as abstraction or abstraction as fuzziness—Heatherwick Studio’s Seed Cathedral (the UK Pavilion at the World Expo 2010), and Sou Fujimoto’s Serpentine Gallery Pavilion 2013. He recounts how Fujimoto said he wanted to make a cloud. “Which is also what I wanted,” Yulo tells the judges.

WATCH: Jorge Yulo on WAF and the benefits of design gatherings

“I imagined the chef thinking of what to prepare with his ingredients on hand, in an open kitchen surrounded by hungry diners, the most well-heeled, the most demanding of Manila, who come with a mountain of expectations. How do you capture what is going on through his head?”

Yulo cuts to a slide depicting his next words: “Just like in a comic book, the chef should have a thought cloud hovering over his head!” The right eyebrow of the judge in the middle, Jason Holley, lifts a tiny bit. “It would billow above like a cloud as opposed to being puffy like smoke, but it would have to look ephemeral like a thought!”

Construction

Apart from the eyebrow lift, the judges are impassive as ever. We are in an inflatable igloo, one of a dozen or more scattered throughout the convention space. Live crits are being conducted simultaneously in these igloos, each with their set of three judges. We can hear the drone of other presenters doing their spiels. Occasionally, we hear applause. One of Yulo’s judges is Japanese, and his interpreter briskly translates Yulo’s speech. She has to be fast, as Yulo is reading rapid-fire from his script. She speaks from behind a fan, ostensibly to direct her voice into her client’s ear.

“With the parameters I was given,” Yulo continues, “it (the cloud) would have to be lighter, quicker to assemble, and cheaper. The project introduction came with a 60-day deadline. Construction took 45 days and cost $130,000. There wasn’t much design time, so I gave myself a lot of flexibility in my version of a cloud to allow for changes during construction.”

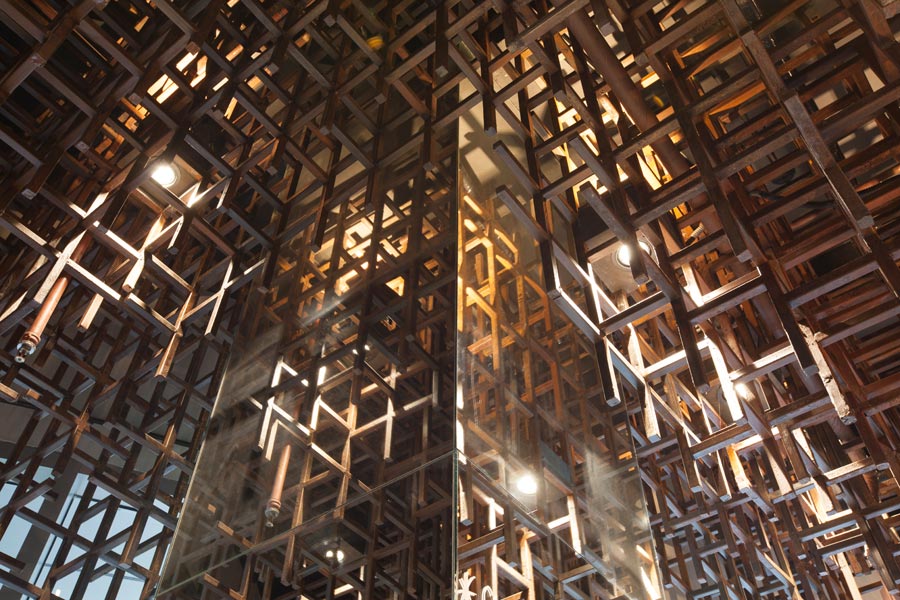

The complex looking structure is quite simple. Instead of constructing a matrix or latticework and attaching it to the ceiling, Yulo used individual steel rods of different lengths. Perpendicular spokes are welded on alternate sides of each rod and spaced in progressively shorter distances towards the lower end of the rod. When positioned just so, rods and spokes appear welded to one another.

Using several wooden sticks—scaled down models of the steel rods—Yulo shows the judges how the rods were attached to the ceiling, and how the cloud was made.

Rusty and rustic

The short show-and-tell perks the judges up. Yulo has made eye contact. He continues by showing various color options. “We tried it in white. We felt it lacked commitment, and it looked like smoke. Red looked like fire. If only red were not so associated with fast food, maybe. Gold was too auspicious—good feng shui, but too mature and refined for the young chef. Black was too scary, and (as a thought cloud) it seemed like the chef was not thinking, and black rods might disappear against the black ceiling.”

Yulo reveals he chose to go with rust—not just the color of rust, but actual rust—justifying it as raw, unrefined and natural—like an uncut gem, like the young chef. Rusty steel looks like wood, Yulo adds, which is not incompatible with Japanese.

Yulo talks about the use of mirrors for certain walls, copper for the bar counter, concrete for the floor, and lighting at different heights within the steel cloud. In closing, Yulo speaks of how, apart from the shōchū wall, the design makes several Japanese references without displaying literal Japanese artifacts.

Question and answer

Confronted by the slew of Japanese references, Michael Goodman and Jason Holley seem at a loss for words and then simultaneously ask fellow judge Yuki Fukumoto to toss the first question. The three chuckle, and the audience as well. The Filipinos in the audience hold their breath. Will last year’s INSIDE winner of the hotel category hold the Filipino architect accountable for referencing wabi-sabi, hanami, and the enjoyment of the transitory?

“This seems like a very high ceiling,” says the interpreter. “What is the highest height?”

“4.8 meters. The contrast between the low spokes and the high ones gives the illusion that the ceiling is higher than it is.”

“Amazing. Only 4.8? But it looks so much higher than that,” says the interpreter while Fukumoto nods, smiling.

Goodman joins in: “And the lowest point is?”

“The lowest spoke is about 1.7 meters high and you can touch it, but it’s over the counter, so you don’t get hit on the head.”

Holley remarks on how small the space is, and notes that Yulo had but “one major design element.”

He asks Yulo what his approach was to make sure that the overall design remained balanced and not overwhelmed by the ceiling treatment. Yulo appears not to have heard the judge over the background noise, as his reply is off tangent: “In between servings, there’s a bit of a wait. The ceiling assemblage is rusty and rustic; I wanted the people to get a little visual entertainment or stimulus while waiting for the next dish to come out.”

Holley persists: “What was your approach to making sure it didn’t become too strong. Because when you have one design idea, there’s a risk that you can become too strong or not strong enough. How did you approach creating that balance?”

“The fact that the cloud was not straight-cut, I think that softened it,” Yulo replies.

“I’m interested in the tight budget and tight timeline for construction, and that to me implies a lot of trust. I’m interested in the relationship you had with your client,” says Goodman.

Yulo’s response is again off tangent: “When we needed to cut down on budget, we reduced the number of spokes. It was very modular.” Yulo would later tell me that he couldn’t make out the question about his client. He didn’t hear the part about trust, which is a shame because it was an opportunity to affirm Goodman’s keen perception, and to talk about how he worked with his clients on the project. Two of the owners, Eliza Antonino and Abba Napa, are good friends of Yulo’s, and had given him carte blanche because they indeed trusted him completely.

In an interview days before INSIDE, Napa told me why they chose Yulo: “I was looking for suppliers of sake and shōchū, and was asking Jorgie for advice, because he is such a lover of sake and—well, all things Japanese, really—then it just made sense, Jorgie should design the restaurant because we trust him absolutely, and he’s such a nihonphile!”

Apart from the two questions that Yulo could have answered better, the Q&A goes well. I am positive the judges are impressed with the ingenuous use of rusting steel rods, and with what was achieved given the budget and time constraints.

“Excellent detail, a wonderful presentation,” Goodman pronounces before thanking Yulo, and declaring the crit sessions closed for the day.

The verdict

Fast forward five hours. The convention hall is noisy with delegates unwinding for the evening. People are drinking beer and wine. Yulo and his companions are the few among the crowd not holding glasses. A voice over the sound system announces the names of Day 1’s winners. Needless to say, we are crestfallen he didn’t win. The winner is Vivarium, a restaurant in Bangkok converted from an old warehouse saved from being demolished by developers building condominium towers on the site. Inspired by a terrarium, the vast, plant-filled Vivarium made use of a lot of artifacts including junk and tree roots excavated from the site. Hard to argue against the jury’s verdict; it is a more than worthy competitor, particularly with the added appeal of adaptive reuse.

READ MORE: Filipino teams test run for WAF 2017 at GROHE send-off

I wonder whether it might have helped Yulo’s cause if he explained the etymology of the restaurant’s name. I wonder whether during deliberations Fujimoto mentioned to his colleagues what Mecha Uma means. Goodman and Holley might have found it amusing. The restaurant’s name is a contraction of the words mecha, which means unreasonably or excessively (and has been adapted in English to mean extremely, as in mecha-groovy); the colorful slang word mechakucha, which means an insane, absurd, f–king mess; and umai, which means good or delicious.

I think the name perfectly describes the tsunami of design billowing over the diners’ heads at Mecha Uma. I also think we should toast Yulo with a round of shōchū when we get home. Banzai! ![]()

This article first appeared in BluPrint Vol 6 2015. Edits were made for Bluprint online.

Photographed by Ed Simon