PH at the Venice Biennale: A comeback after 51 years

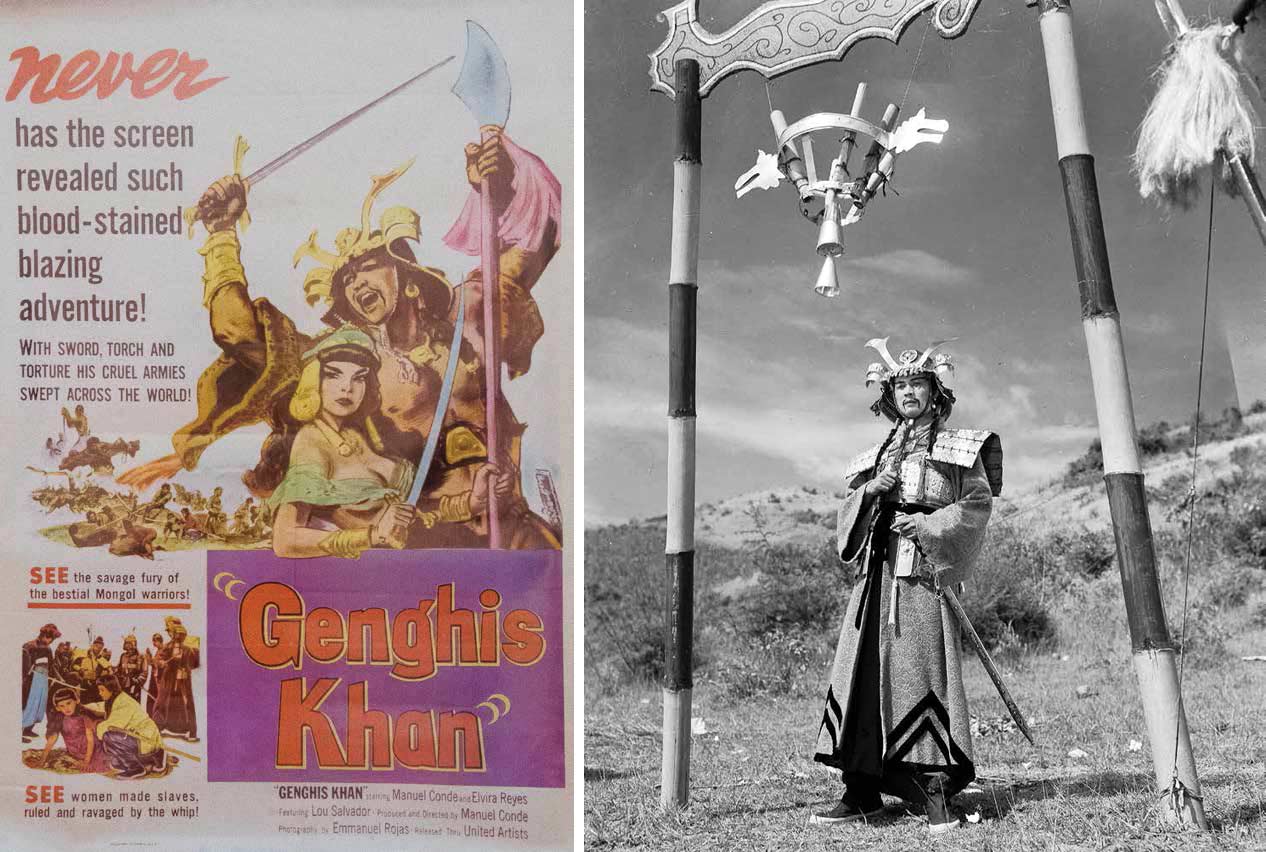

The Philippines’ participation in the Venice Biennale is studded with jump-starts and an extended cliffhanger. We made our Venice debut at the 1952 International Film Festival. Manuel Conde’s Genghis Khan, dramatizing the making of the Mongolian conqueror, competed on the international stage with films by Chaplin, Ford, Fellini, and Bergman.

Conde attended the premiere on the Italian island with vice consul Manuel Alsate. Historian Agustin V. Sotto recounts that the two-man-barong-clad delegation was “happily surprised to see the Philippine Flag by the Palais du Congres in Lido.”

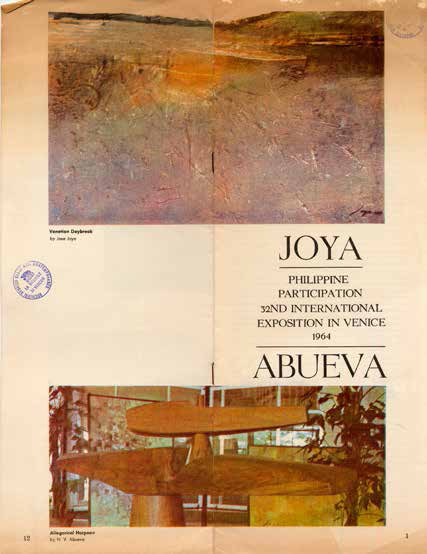

In 1961, Purita Kalaw Ledesma, art critic and founder of the Art Association of the Philippines (AAP) wrote the Venice Biennale and received an invitation the year after. However, we were only ready to participate in 1964. Painter Jose Joya and sculptor Napoleon Abueva, now both National Artists, were that year’s representatives to the world’s oldest (dating back to 1895) and preeminent stage for contemporary art.

Funding was tight, with no support coming from the government. Poet Emmanuel Torres, who was commissioner for the Philippines’ first pavilion, felt as if he, Joya, and Abueva “had just been pushed overboard … bag and baggage into the Grand Canal.” The modest space was supposed to exhibit nine oil paintings and five molave sculptures, but the AAP failed to ship two of Abueva’s pieces.

That year was the moment of American Pop Art as Robert Rauschenberg received the grand prize. And so the works in the first Philippine pavilion made their way home and into collections across the metro. Joya’s Granadean Arabesque is now with the Ateneo Art Gallery, and Hills of Nikko on view at the National Museum. Abueva’s Allegorical Harpoon is a mainstay at the Cultural Center of the Philippines.

Then, the Philippines was unseen at the Venice Biennale for 51 years.

In 2013, Senator Loren Legarda paid the Biennale a visit and wondered about the country’s absence. She wrote: “I had noted then that even small countries such as the Maldives and Tuvalu had their respective exhibits, so it seemed odd that the Philippines, a nation rich in culture and in people with remarkable artistic talent and skills, was not part of the oldest, most prestigious art biennale in the world.”

The comeback was planned and executed by a committee composed of members from the National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA), Department of Foreign Affairs (DFA), and Office of Senator Legarda. They wrote a joint letter of intent to Paolo Baratta, President of La Biennale di Venezia, in 2014. And the Philippines was once again invited to participate in 2015.

For two consecutive editions since then, the country has joined the global conversation discussing the state of the world and its people through the Philippine Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. Art and architecture take turns every other year. 2018 marks the Philippine architecture’s second appearance with The City Who Had Two Navels at the 16th International Architecture Exhibition.

But before we bring you updates from Venice this year, here’s a run-down of the previous years’ curatorial briefs.

Tie A String Around the World (2015)

Artists: Manuel Conde, Carlos Francisco, Manny Montelibano and Jose Tence Ruiz

Curator: Patrick D. Flores

Commissioner: Felipe M. De Leon, Jr.

Venue: European Cultural Centre – Palazzo Mora

In 1950 in the Philippines, the filmmaker Manuel Conde and the painter Carlos Francisco worked together to do the first film ever on Genghis Khan. Telling the tale of the conqueror’s rite of passage from warrior to overlord in the form of a metrical romance and an adventure, it bemused both Hollywood and Venice. The Philippine Pavilion returns to Venice after 51 years through this exemplary film to reflect on the country’s modernity and the present scheme of a world redrawn on the surface of water.

Around this premise, Jose Tence Ruiz intimates the specter of the Philippine ship on the South China Sea, at once “slum fortress” and armature of archipelago. Manny Montelibano refunctions the sound and image of a threshold of territory to scan both the epic of survival and the radio frequency of incursion. Surveying his dominion at the end of the seminal film, Genghis Khan professes to his beloved that he would tie a string around the world and lay it at her feet, a gesture of intense affection, of breathtaking hubris.

Muhon: Traces of an Adolescent City (2016)

Architects and Artists: Poklong Anading, Eduardo Calma, Tad Ermitaño, LIMA Architecture, Mañosa & Company, Inc., 8×8 Design Studio Co., Mark Salvatus, C|S Design Consultancy, Inc., Jorge Yulo

Curators: Sudarshan Khadka, Jr., Juan Paolo de la Cruz and Leandro Locsin, Jr. of Leandro V. Locsin Partners (LVLP)

Commissioner: Felipe M. De Leon, Jr.

Venue: Palazzo Mora

The Filipino word “muhon,” derived from the Spanish “mojón” and translated roughly as “monument” or “place-marker,” evokes contemplation through the primal act of marking a fixed point in both space and time. Symbolically, the construction of a “muhon” can be considered an act of affirming one’s existence: it conveys the idea of staking a claim in the universe. The exhibition is anchored in the notion that the built environment is a critical method of understanding one’s sense of and belonging to a place. It is a way of tracing a presence, standing a ground, abiding by a position.

READ MORE: A primer on Muhon — Philippine architecture’s Venice debut

The country’s capital Metro Manila arose from the ruins of an older colonial city leveled by the Second World War. Growing in frenetic pace since then, it is conceived in its current context as an adolescent city, restless, and awkward and in many ways raging.

The nine participants selected and surveyed buildings, structures, landmarks, boroughs, and urban landscapes. Evaluating their cultural merit and analyzing their potential within the national heritage, they created three sets of abstracted models built for each of the subjects corresponding to their original state, their current condition, and projected future.

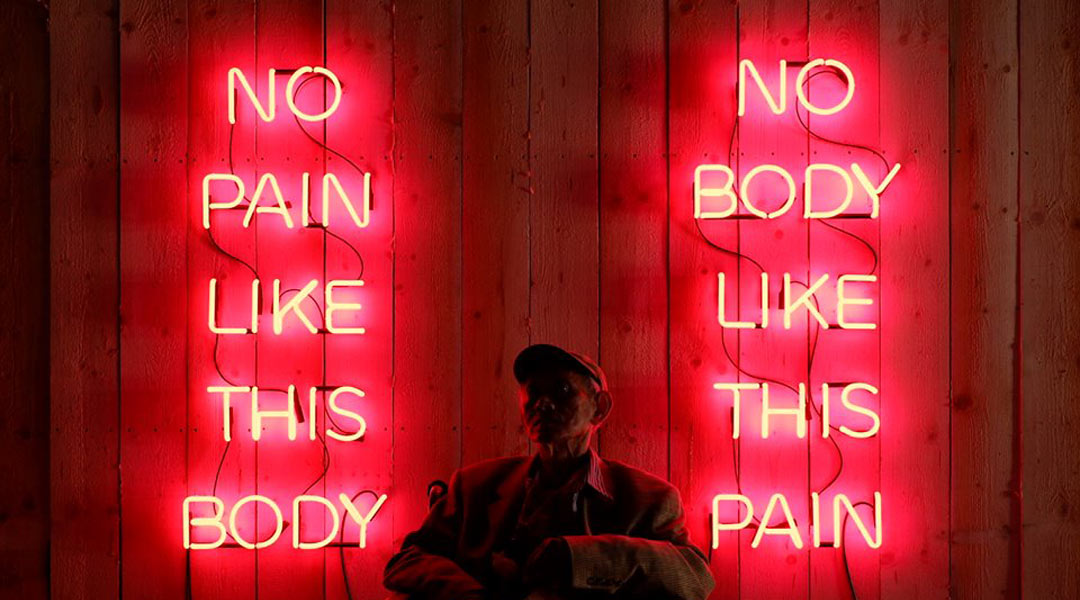

The Spectre of Comparison (2017)

Artists: Lani Maestro and Manuel Ocampo

Curator: Joselina Cruz

Commissioner: Virgilio S. Almario

Venue: Artiglierie Arsenale

Spectre of Comparison encapsulates the experience of Rizal’s protagonist, Crisostomo Ibarra, when he gazes out to look at the Botanical Garden of Manila while simultaneously remembering the gardens of Europe. This double-vision of experiencing events up close and from afar, no longer able to see the Philippines without seeing Europe nor gaze at Europe without seeing the Philippines, was pointed out by historian Benedict Anderson in his essay “The First Filipino” (1997): “Here indeed is the origin of nationalism, which lives by making comparisons.” Rizal, the nineteenth century indio from the colony, with some melancholy, comprehended the colonising European other.

With this as pivot, Lani Maestro’s and Manuel Ocampo’s practices, aesthetically worlds apart and produced through a multiplicity of contexts, have at their core this “spectre of comparison.” Both artists were politicised by the specific moments of their departure from the Philippines: Maestro leaving at the height of the Marcos dictatorship, Ocampo during the 1980s, after the Marcos regime was ousted in a revolution mounted by a society deeply dissatisfied with the ensuing corruption that followed Martial Law. Although their practices developed at different moments, they were forged within the “collective” experience of the émigrés spectre.

Maestro’s practice moves fluidly through various artistic engagements incorporating sound, film, text and photographs. While Ocampo paints canvasses that criticise systems through forceful figurative images. The exhibition looks at their practices as emblematic of the exprience of Rizal’s “spectre of comparison,” with the juxtaposition of their works as a manifestation of sociopolitical commentary on the Philippines and of the many localities where the artists have based since, as seen “through an inverted telescope.”

READ MORE: PH returns to Venice Biennale with The City Who Had Two Navels