Architecture education should adapt to the realities of the profession

Any discussion about architecture education inevitably lead to reflections on the state of the profession in the Philippines, and to the experiences of Filipino architects around the world. Allow me to project in multiple tangents so I could meander back into some thoughts on how we could work together to improve architecture education standards in the Philippines.

Move up, move home

Filipino architects are recognized around the world as talented, creative, and hardworking professionals. Since the rise of the Asian tigers and the Gulf States in the 1980s and 1990s, our architects have been leaving our shores to eke out a living. The contributions of these expatriates to their adoptive economies are immeasurable. Foreign bosses and colleagues appreciate the gusto with which Filipinos apply themselves at work. For most Pinoy expatriate architects, it was more than just a matter of survival. It was the chance to be relevant—the chance to practice their craft at the bleeding edge of the design profession.

Despite the lack of accepted international credentials, a handful of these overseas professionals moved up the ranks to assume leadership roles in their respective firms. These exceptional architects have shown that in a meritocracy, one can indeed go far with talent and experience. Still, most of these expats shared the dream of moving back home to start their own practices. A handful of them has been able to do so, harnessing their learnings and connections gathered abroad. Many Filipino firms whose projects are featured in this magazine are products of this diaspora.

YOU MIGHT LIKE: A manifesto for architecture education in the 21st century

The dream to come home is always alive partly because an architecture degree and license from the Philippines allow you to practice and use the title ‘Architect’ only in the Philippines. The reason is our academic programs neither fall under the internationally accepted standards set by American (National Architectural Accrediting Board) nor British (Architects Registration Board and Royal Institute of British Architects) accreditation bodies. Some see this as a matter of independence. I, however, see it as a question of competence in international markets. How do we prove that homegrown Filipino architects are indeed world-class if our paper qualifications don’t get us on equal footing with peers in other countries?

Cross-border equivalency

If we’re serious about being internationally competitive, why can’t we make a concerted effort to apply our programs for NAAB or ARB/RIBA accreditation, or at least apply for professional equivalency evaluation? The NAAB has been accrediting programs outside the United States, such as Canada and Mexico. The RIBA has accredited programs in 17 countries, including China, Singapore, Malaysia, and South Korea. Accreditation doesn’t necessarily mean referencing American and British qualifications. On a basic actionable level, it would help future Filipino architects if the Philippine Regulatory Board of Architecture would get their act together with their counterparts in the ASEAN Architect Council to institute a common curriculum based on common standards and skill requirements. We are ill-prepared for ASEAN integration, which takes effect at the end of this year. Singapore firms have a foothold in Vietnam, Brunei, and Myanmar, and because of this, locals in those countries now take their methods as the acceptable practice. This is while we are still happily working within our little bubble of Philippine “independence.”

Semi-ripe mangoes

The diaspora of Filipino architects has hollowed out the engine rooms of local design firms. Commonplace are local firms with a handful of principals on top, and a large number of 35-and-

under Millennials below. Very few from the older generation who left the Philippines came back.

Fewer still (because of the bleak economy) were able to get their hands on local work and develop

their skills to become competent managers in these firms. That gap in upper and middle management is now being filled by architects of my generation (those with ten years’ experience) and younger, who are being primed for roles that require more experience.

Some young architects, seduced by the blossoming startup culture, heed the entrepreneurial call and forego the whole in-office maturation process to start their own practices, only to realize that the education and training they received are insufficient preparation. In school, we’re asked to submit

profiles and brochures of our “future” design firms, but we’re not taught how to write project proposals; how to charge for services (because the UAP documents are outdated); how to manage projects; hire and mentor staff; and balance the books. The academe says these are learned during apprenticeship and practice. But last I checked, Professional Practice is a course subject. So, what are we teaching?

How can you think outside the box and conceptualize something unique (which is what most students think of their work) if your box is still empty of ideas and tools?

What are we practicing? Why is there such a disconnect between school and practice? We need to strengthen the preparation and training of architects for practice. The Ateneo School of Medicine and Public Health, together with its Graduate School of Business, has pioneered a course that combines clinical education of future medical doctors with the practical rigors of an MBA. They have acknowledged that the medical practice is, in effect, a business. Architecture schools could and should do this, too.

Filling empty boxes

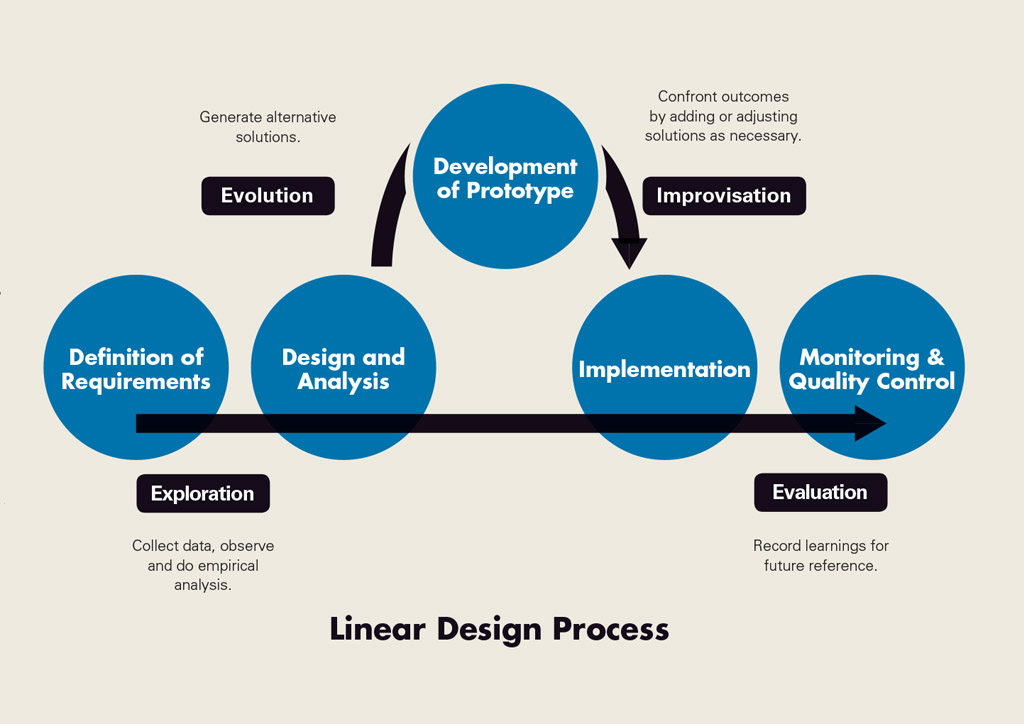

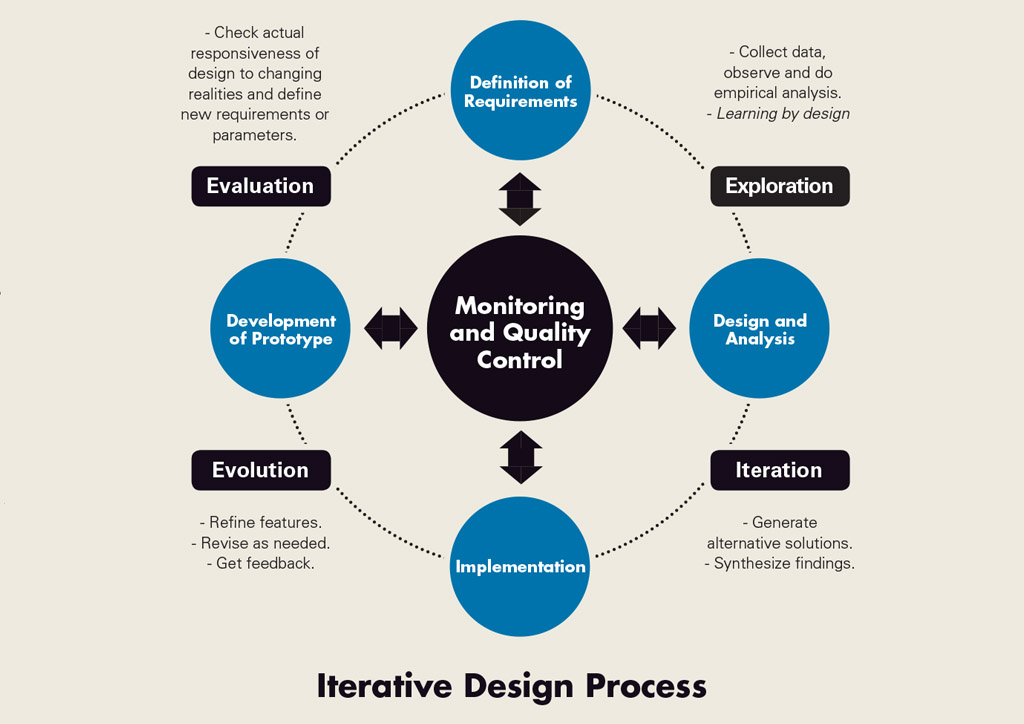

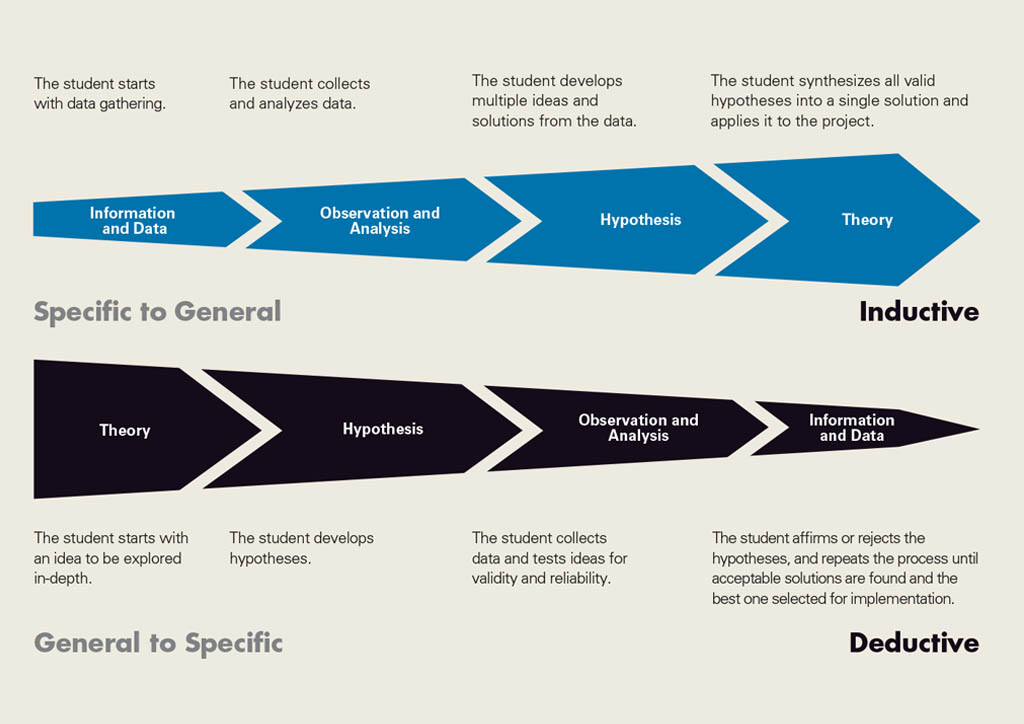

In design education and discourse, the method of teaching is centered on developing a design philosophy and concept. It’s usually an inductive process where the design is driven by the germ of an idea. I’ve seen design classes spend countless hours talking about concept, only to realize during the space programming and design stage that the concept so eloquently crystallized falls apart because it’s a horrible fit to the site, the scale of the project, and the various uses to be satisfied.

While teaching high-rise design (Arcdes 7) in College of St. Benilde School of Design and Arts, one of the points I would emphasize is that some concepts don’t work for some projects. You can talk about creating a Filipino skyscraper, but it all falls apart if you insist on creating a bahay kubo 35 stories high. It’s ignorant of so many other layers of information.

READ MORE: Making an Architect, Testing an Architect

We hammer at the need for a thought process distilling ideas into a singular object or theory for the project, but we fail to teach students how to process various layers of data needed to design in an informed manner. How can you think outside the box and conceptualize something unique (which is

what most students think of their work) if your box is still empty of ideas and tools?

Let’s teach students to research from Design 1, and not at Design 9. The box has to be filled first with

sufficient substance to be distilled into something unique. Instead of striving for creative expression,

schools should train designers to process larger bandwidths of information and synthesize ideas into solutions. This can only happen in a research-driven, deductive, and iterative process. Not the linear or inductive process we’re used to in most schools.

Design honesty comes from knowing how it’s put together

Woe is the young architect who, working for his first client, finds out that design is non-linear, and

that in some cases, the concept is not his, but the client’s. Too many egos have been fed and enlarged

to believe in the superiority of the inductive process in creating architectural icons. Likewise, many

owners have scratched their heads and lost money condoning the architect’s “iconic” vision, when

what they needed was simply a functioning piece of architecture that serves their needs and not the

architect’s ego.

Architecture studios at the National University of Singapore (NUS) are tasked not only to design,

but also to detail and show how everything is put together. I’m impressed by the level of technical

knowledge that NUS students show in their presentations. Design and Building Technology

lectures are fused and applied together in the studio. That way, they learn to be honest designers. They do not design buildings with amazing cantilevers made of chipboard, or with sleek, diagonal cladding wrapping a basic shell. They are challenged to draw something elegantly in detail. Instead of cowering within the box of buildability, these kids dig deep to figure out how to execute their designs using models and mock-ups.

Geo-location

Taking the idea of design honesty further, why not bring the students to the field and build their designs themselves? One of my favorite examples of this is Samuel Mockbee’s Rural Studio in Auburn

University, Alabama. What started out as an outreach activity where students patch together recycled materials to build houses has turned into a formal program with students spending a year or more building homes and civic buildings for the poor. Students learn how to do joinery, pour concrete, weld steel, and lay roofs.

While it’s difficult to execute a program of similar intensity (because of time and resource constraints), why can’t we institute a design-build exchange program between the major urban Centers of Excellence and the regional Centers of Development? Architecture students from main urban centers could rotate to schools in the provinces, be tasked to build actual designs using local or vernacular methods, experience the difficult building conditions and see the socio-economic problems far afield.

YOU MIGHT LIKE: “Plus Ultra” – Geronimo Manahan told U.P. Class ’99

Meanwhile, corresponding students from the provinces could rotate to schools in Manila and Cebu

to see the cutting edge in design, technology and inspect actual construction of complex projects.

This would enrich the less-developed programs by exposing them to methods in the Centers of Excellence, and could hopefully trigger a heart-shift in the purpose and inculcate a sense of social purpose and responsibility—values usually lost to the attention-hungry, money-driven architecture

that the bigger programs aspire to.

Another form of geo-location would be for schools to locate design studios closer to the cores of

major practices like Makati CBD and Ortigas CBD. I’ve met countless young, idealistic, capable practicing architects who would like to teach but are turned off by the inconvenience of travel to the University Belt in Manila or Quezon City. By locating closer to the epicenter of dominant practices, we can strengthen the full-time academic faculty of schools with active practitioners. This is a good way to attract a different dimension of faculty. Schools can’t pay adjuncts or part-time lecturers more than full-time academicians, so let’s make it easier for those with thriving practices to share their knowledge with students.

Specialization, stratified degrees, and licensing

The ongoing building boom in our country has seen the rise of various roles that architects play in the property sector. Aside from the traditional roles of design managers and contractors, architects are

now finding niches in the full cycle of development. We see architects as construction managers,

quantity surveyors, interior fit-out designers, urban planners, real estate executives, brokers, property

managers, etc. There’s also a growing demand for specialists and technicians focused on visualization

and BIM (building information modeling).

As demand rises for people with such skills, the blanket solution would be to churn out and

register more architects into the licensure roll. Architecture schools have been doing this, packing

classrooms with more chairs and drafting tables, without addressing the deteriorating quality of

our graduates measured against international standards—not the local board exam. These schools

are not doing the profession a favor. Producing quantity over quality takes away from the respected

title of Architect and lessens our credibility in the international arena.

In Indonesia, fresh architecture graduates are automatically licensed to design a one to two-story

residence. With added experience, they can take the licensure examinations for the next higher strata

of practice, which, when passed, permit them to handle buildings and developments of increasing

complexity and risk. Thus, the title Architect is a rank indicative of competence, continuing professional development, and experience, which the professional must accrue over the years. It is incomprehensible that our Continuing Professional Development program is still on hold, our professional organizations offering ad hoc CPD courses that would not stand the scrutiny of accreditation bodies elsewhere in ASEAN.

READ MORE: WAF has a student competition that the PH already won

Offering stratified degrees would address the demand for increasing specialization in roles. Not only could schools offer introductory electives in their undergraduate programs, but they could also offer specialist degrees to give students viable options off the main track of architectural design practice. The architecture education landscape in Singapore for example includes courses in Architectural Technology and Visualization or Architectural Studies offered by various polytechnic schools. They acknowledge the demand for highly skilled technologists, visual artists, and production specialists needed by the industry. The best job captains I’ve met are holders of specialist degrees; some are now working towards a full architecture degree.

The title “Architect” used to mean an expert versed in the art and science of designing and building. But nowadays, being a licensed architect doesn’t mean you get to practice as one. There’s nothing wrong with that. To practice may be the dream scenario, but it is not for everybody.

There is no harm in recognizing one’s interests and limitations and casting off toward one of the specializations mentioned earlier. The envelope and marketplace of ideas for design-related services

and know-how have expanded, allowing architects to find their little patch of Eden. The opening of

career options for architects requires opening the educational landscape and changing long-

established notions of success and achievement. We should educate architects to find their role in the

design universe, doing what they are good at, and what makes them happy.![]()