Charles Jencks critiques big architecture

“Astonish me, excite me, show me something I haven’t seen before! And make it cheap, efficient, functional, and green!” is how architecture historian and critic Charles Jencks parodies modern developers. Impossible briefs like these result in trophy buildings or stillborn icons, Jencks calls them. Icons make authentic statements.

Trophy buildings are failed icons because “they don’t take risks” and are but “frozen gestures.” We’re seeing more and more trophy buildings not only because we are living in the Age of Iconic Buildings, but also because we are living in the Age of Bigness. With 3.5 billion people in the world living in cities today, and that number expected to double by 2050, buildings are getting incredibly bigger and taller.

The problem with bigness, Charles Jencks says (taking a page from Rem Koolhaas), is “it breaks with scale, with architectural composition, with tradition, with transparency, and with ethics.” According to Jencks’ Law of Diminishing Architecture, the bigger a building is beyond half a million square feet (about 50,000 square meters), the worse it gets. If the result isn’t stillborn, the big building is afflicted with Monothematitis.

There are exceptions to Jencks’ Law—not all big buildings will offend or bore us to death. But the developer must pour so much, much more money into the building for it to “become individualized, varied, plural, mixed, related to ethnic identity, ornamented, enigmatic, evocative, full of feeling and green elements.” Still, many of our modern big buildings today fall short. They are “big in scale, repetitive, anonymous, abstract and stereotyped, following the Modernist universalism of mass production.” Jencks calls this style Generic Individualism, a trend that every major global city is headed towards.

READ MORE: Lessons on small design from WOHA (and Nick Joaquin)

Here’s what he had to say about some of today’s iconic projects:

De Rotterdam Towers by OMA

Definitely a bad case of Monothematitis, an architectural disease of repetitive stereotypes. “Bigness run amuck!” exclaims Jencks, citing the towers to illustrate Rem Koolhaas’ observation, which he agrees with: “Bigness is no longer part of any urban tissue. It exists. At most, it coexists. Its subtext is, ‘F*ck context.’”

Pinnacle@Duxton, by ARC Studio Architecture + Urbanism with RSP Architects Planners & Engineers

Generic Individualism. Says Jencks: “You see in the Pinnacle, a kind of deficit. It is generic, but more articulated, and individualized with all sorts of not-quite personalized mixtures. You can see why Lee Kuan Yew said in the 1960s, ‘We cannot afford the luxury of poetry.’ He was saying they needed to focus on economic and social transformation first.”

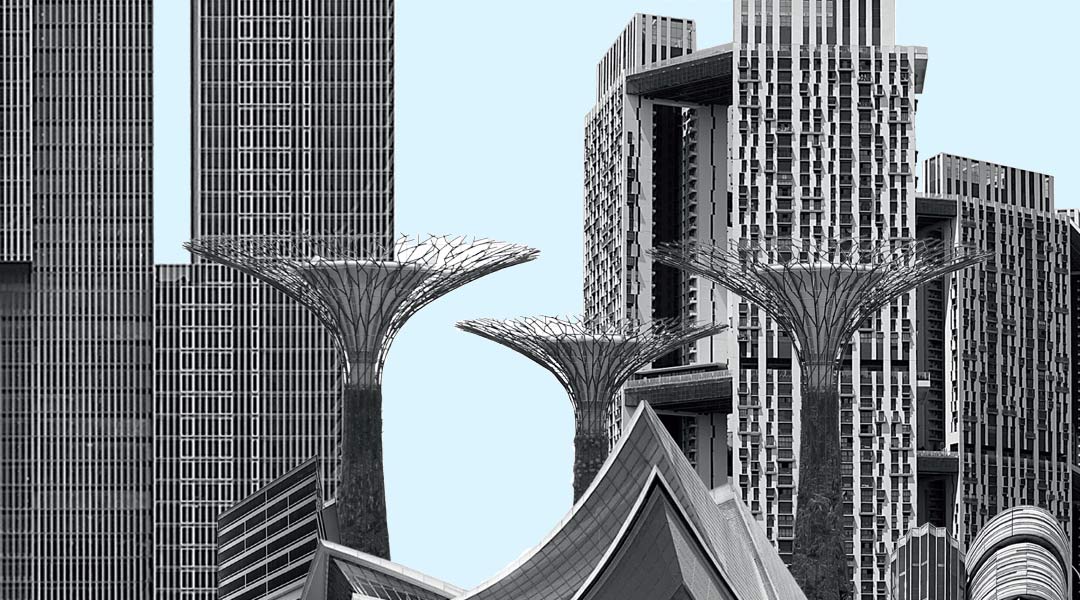

Gardens by the Bay by Grant Associates and Wilkinson Eyre

Poetry. “There is no short formula for making great architecture. It has to be the poetry we can now afford. If you’ve reached generic individuation, you can go the next stage and have personization. Singapore has an incredible, poetic creation, which is on a global level the best of its kind, on which a billion dollars was spent to make poetry. The iconography, even down to the purple and green Super Trees was based on plants endemic to Singapore. It is a meaningful and symbolic ornament, architecture and icon, and it works.”

NTU Learning Hub by Thomas Heatherwick

Generic Individualism. Jencks’ comment: “Heatherwick was trying to attain poetry by working with artists in the mass production of the concrete. They produced a thousand different panels using transformable formwork. When you see it, it’s more randomized, though, than personalized. It’s nice to have pink concrete and patterns changed by computer, but it’s still not communicating an overall message. It’s still generic.”

When Jencks spoke at the 2015 World Architecture Festival held in Singapore, the city-state was celebrating its 50th anniversary. He acknowledged its enviable success at creating a built environment that has been faithful to the government’s social contract with its citizens—it is the only country that has rapidly urbanized while providing for its people, and even increasing its open, green spaces. “Singapore definitely is the center of this oxymoronic style more than any other city in the world,” he said.

However, given the the social contract Singapore has with its people, which other cities don’t have, Jencks argued that it was time for Singapore to take the next step. That next step is poetry. ![]()

This article first appeared in BluPrint Vol 2 2016. Edits were made for Bluprint.ph.

READ MORE: Missed Singapore Design Week 2018? Here are 4 more design events you can attend