The geography of risk and resilience in Guiuan, the first town hit by Haiyan

In the early morning of November 8, 2013, Typhoon Haiyan first made landfall in Guiuan, a town of over fifty thousand residents in Eastern Samar. It is the strongest storm ever to make landfall in recorded history. At the height of the super typhoon, a monstrous storm surge gushed 100 meters inland scouring coastal settlements along its path.

Concrete structures were no match for the sheer force of the wind, which, at 315 kilometers per hour, turned large, heavy debris into deadly projectiles and reduced Guiuan’s local gymnasium, a good 330 kilometers offshore, into rubbles. Based on reports, 101 people perished while 17 remain missing, presumed to be dead. In total, the typhoon left 118 casualties in its wake.

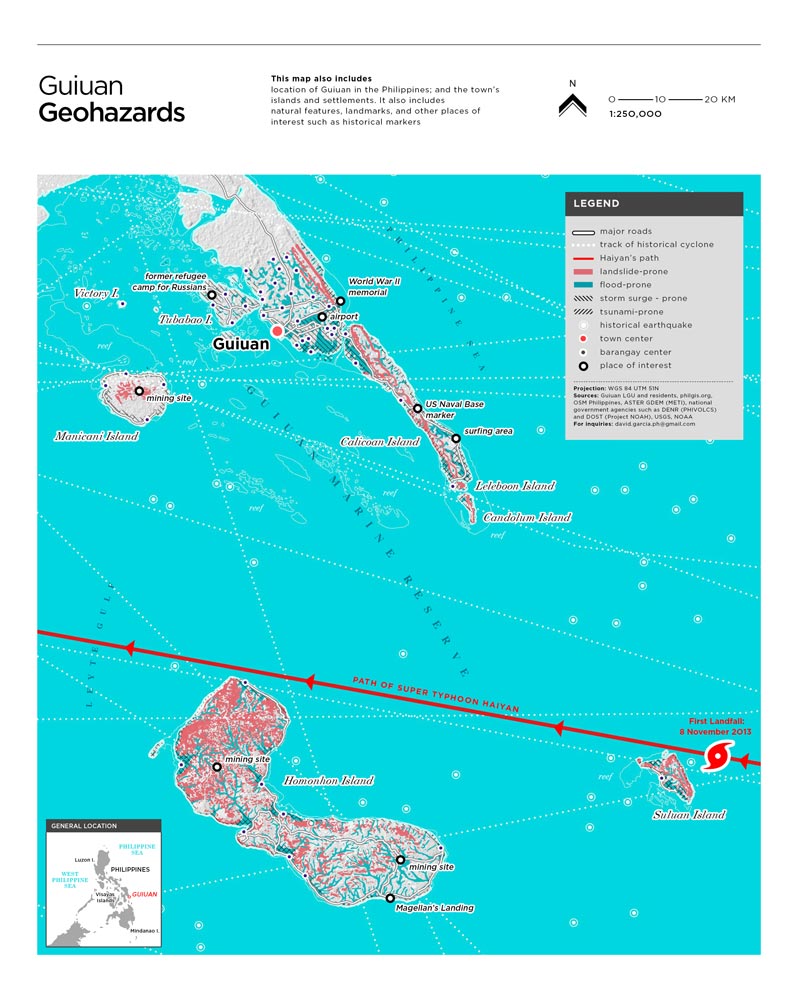

Like many towns in the archipelago, Guiuan is exposed to a multiplicity of hazards. The town’s coastal zones are exposed to storm surges and tsunamis. The uplands are susceptible to landslides and the lowlands to flooding. Strong winds can reach across coastal and upland ecosystems. Faults and trenches surround the town, and earthquakes are frequent.

In 2012, tremors from a 7.6-magnitude earthquake, which emanated from the Philippine Trench 70 kilometers away, reached Guiuan and its surrounding regions. Having lived through numerous disasters, the townsfolk have come to terms with the hard truth: There are no safe or unsafe zones; there are only places of varying risk, and the people’s capacity to adapt in their places.

READ MORE: Did we even learn our design lessons after Typhoon Ondoy?

Risk-based Paradigm: A post-hazard view of disasters

Building resilience means reducing risk—the likelihood of deaths, injury, and damage to property caused by hazards. A disaster’s severity hinges on the levels of risk present before the disaster happened. Risk can be exacerbated or mitigated depending on human factors such as state policies, land use, and architecture. The presence of risk depends on four major factors—hazards, exposure, vulnerability, and capacity.

Hazards. Typhoons, storm surges, and earthquakes are not by themselves considered disasters. They are hazards—dangerous phenomenon categorized according to geology, climate, and sometimes human action such as nuclear waste. Hazards only result in disaster when life and property are affected. Haiyan brought to Guiuan multiple hazards—floods, winds, and surges—all at the same time.

Exposure. If there is a community, property, or ecosystem that is in the way of the hazard, then that means that there is exposure. In Guiuan, communities from the ridge to the reef are exposed to multiple hazards. Each of the 60 barangays in Guiuan is exposed to at least two types of hazards.

Vulnerability. Within people and places exposed to hazards, there are groups and households that are far more susceptible to damages. Predisposition to such damages is called vulnerability. The people of Guiuan are exposed to three types of vulnerability.

- Without means to build stronger houses, many families in Guiuan are rendered vulnerable. Those in extreme poverty do not have enough to purchase or rent on lands in low-risk areas so they stay in areas highly exposed to frequent hazards.

- Even before Haiyan, the marine ecosystems of Guiuan have been severely damaged due to illegal fishing practices. Mining is so prevalent in the town’s islands that citizens have repeatedly raised concerns over the effects of the extractive activity on agricultural land, water supply, and marine resources. The conflict between mining companies and the locals is mired by political tensions. All of these affected the town’s development potential well before the super typhoon and are deep causes of vulnerability.

- Technical/educational. A large number of the population and even the local government itself do not have access to critical geographic information on local geohazards.

READ MORE: Sitio Ubos: What remains when heritage conservation fails

Capacity. Aside from evacuation measures, Guiuan didn’t have the capacity to implement proactive measures on reducing risk. The local government has not enforced the law on building easements. More importantly, the town doesn’t have enough budget, information, technology, and infrastructure to sustainably develop settlements with better shelter and services in places with plenty of economic opportunities and less risk. Since a majority of the population depends on fishing and trade for livelihood, both slum dwellers and property owners erected homes near the shoreline.

The disaster brought by Haiyan in Guiuan was not caused by so-called natural causes. It was caused by a combination of the following: the severe magnitude of multiple hazards, high exposure, high vulnerability, and relatively low capacity compared to the hazards. Because it is futile to stop hazards from coming in, the ultimate goal in a risk-based mindset is for people to adapt in their places by reducing exposure; addressing vulnerability; and building capacity. However, popular measures in reducing exposure tend to be tricky, slow, and costly.

The complexities of reducing exposure

Tricky. The dichotomous policy classifying zones as safe or unsafe presents tricky options and false expectations of safety, yet it is something the government espouses. Immediately after Haiyan, the environment department (DENR) recklessly designated areas 40 meters from the shoreline as a “No Build Zone” (NBZ). Hazard maps made by the DOST and the DENR indicated that coastal hazards like storm surges could go well beyond 40 meters offshore.

However, in Guiuan, the DENR rejected its own hazard maps and erected muhons (boundary monuments) to demarcate the 40-meter NBZs regardless of the type of land or ecosystem.

Later, the Office of the Presidential Assistant on Rehabilitation and Recovery (OPARR) announced that the NBZ shouldn’t be consistently applied across all Haiyan-affected areas. Disjointed efforts in mapping risk and blanket applications of NBZs do not help in the post-disaster situation. If anything, it causes widespread confusion, erodes the government’s credibility, and allows risk to be merely maintained, created, or shifted geographically.

READ MORE: Does Manila really need another reclamation?

Another tricky measure in reducing exposure is the transfer of citizens to relocation sites. In Central Luzon, developers advertise residential subdivisions as flood-free, oblivious to the fact that these subdivisions have been sitting on floodplains since time immemorial. It’s similar to the case of relocation sites in Guiuan and other parts of Eastern Visayas. The sites may be safe from storm surges but oftentimes, they are still prone to flooding or landslides.

Slow. Megaprojects such as the construction of seawalls and reclamation, which may reduce the impact of hazards especially in coastal areas, are too expensive and would require a long time to complete. Proper implementation of such projects would take years to account for huge environmental, social, and economic costs.

READ MORE: The politics and problems of placemaking in the Philippines

Costly. Going back to the policy of relocation, it is expensive to purchase lots that are both near enough to opportunities and services and far enough from coastal hazards. Since current rules on relocation only provide for a limited budget for land acquisition, relocation sites tend to be situated in areas far from where people used to live.

Such relocation sites require large investments in water, power, sewerage, social services, alternative sources of livelihood, and other important ingredients of a fully functioning settlement, all of which cannot be provided by a financially-crippled government. No wonder thousands of units in relocation sites in Eastern Visayas are still empty.

The problem with the relocation model. Despite relocation, people affected by Haiyan are back in coastal settlements. They rebuilt their homes with their own hands and meager resources. Asked why they returned, people say they’ll die in relocation sites all the same, albeit slowly. Their capacities are underappreciated as the decisions on the location, design, and other details on relocation are in the hands of a few.

While the State compels them to move, those who own businesses and prime lots in the so-called danger zones were exempted. For decades, the ruling idea is consistent in such script: typhoons are coming, especially for those without land and property. Informal settlers have to go away but the seafood restaurants may stay. The situation is the same for other provinces affected by Haiyan such as Samar, Leyte, Cebu, Negros, Panay, and Palawan. Despite consultations, decision-making is generally top-down as people do not have a say over the selection of site and the houses’ design.

In addition, they are left to fend for themselves in a waterless, powerless, and jobless settlement. In this milieu, the risk is merely maintained, transferred, and created.

READ MORE: Harvard GSD Dean on why “sustainable” is not enough

Houses designed for disaster. Other people turn to another option: hazard-resilient homes. After Haiyan, many architects were quick to enter the scene offering design ideas like ambulance chasers. Few stayed on the ground long enough to fully understand the complexity of the situation and the needs of the people.

Then, there were open calls for disaster-prone housing design competitions. Considering the wide range of our archipelago’s hazards—flood, strong winds, storm surge, landslide, earthquake, tsunami, liquefaction, subsidence, etc.—such designs often require expensive engineering. In the foreseeable future, reducing exposure will remain an exercise riddled with complexities and false expectations. In contrast, addressing vulnerability and building capacity are easier to accomplish.

People in places as agents of resilience

While there are difficulties in reducing exposure after Haiyan, Guiuananons are building their capacities, lowering their vulnerabilities, and trying to slowly reduce exposure in the process. It’s an inspiring narrative, albeit less flashy, brewing in the background, a story about community initiatives that treat people as agents of resilience in their own places.

Addressing vulnerability. After the typhoon, thousands of fisherfolk created a huge organization, the Guiuan Fisherfolk Federation. As a large force, they deal with social, economic, and environmental issues affecting Guiuan. To provide livelihood for their members, the Federation guards the marine reserves and operates fish cages that can be lowered before a storm. Their work contributes to lowering the economic vulnerabilities of fisherfolk families.

The Federation takes care of the largest marine protected area and barrier reef in Eastern Visayas. Allied with the Federation is a local association of seaweed growers. They have devised a way to likewise lower the frames for growing seaweed before a typhoon. The association provides continuing training and assistance to seaweed processing businesses, an alternative to fishing.

Building capacity. Guiuan is the surfing capital of Eastern Visayas. Hence, the local tourism council actively supports local initiatives in creating value out of their place-based assets. The Diocese of Borongan, which exercises jurisdiction over Guiuan, assists in the self-recovery of households by training them in constructing stronger houses with the help of an international organization. The families have a strong say in the design, budget, and selection of the contractor.

Addressing vulnerability, building capacity, and reducing exposure altogether. A strong association of women in a transitional site deals actively with matters of shelter, services, and livelihood to keep the new settlement alive. The association decides collectively and transacts with the local government and non-government organizations for their needs. They actively work in securing a permanent site less exposed to coastal hazards.

These initiatives are supported by a dedicated core group of local government officers. The local government is building evacuation centers in low-risk areas. They recently finished their first with the support of the United Nations. In 2014, a year after Haiyan, they pulled off a successful evacuation effort before Typhoon Hagupit hit the town. There were torrential rain, storm surges and severe winds for 12 hours, but the casualty was zero.

In Guiuan, resilience is not only built by design but also nurtured by relationships. Theirs is a model based on a better understanding of people in places as agents of adaptation.

The townsfolk were able to organize themselves into institutions capable of addressing vulnerability and building capacity. It is a response that is more systemic, effective, and sustainable in reducing risk. It is a model that runs contrary to the hazard-based mindset of merely treating the situation through any bureaucratic, financial, and technical trap. ![]()

This article first appeared in BluPrint Vol 5 2016. Edits were made for Bluprint online.

Photographed by David Garcia