Critical Thinking in Design: Finding the rationale behind every design decision

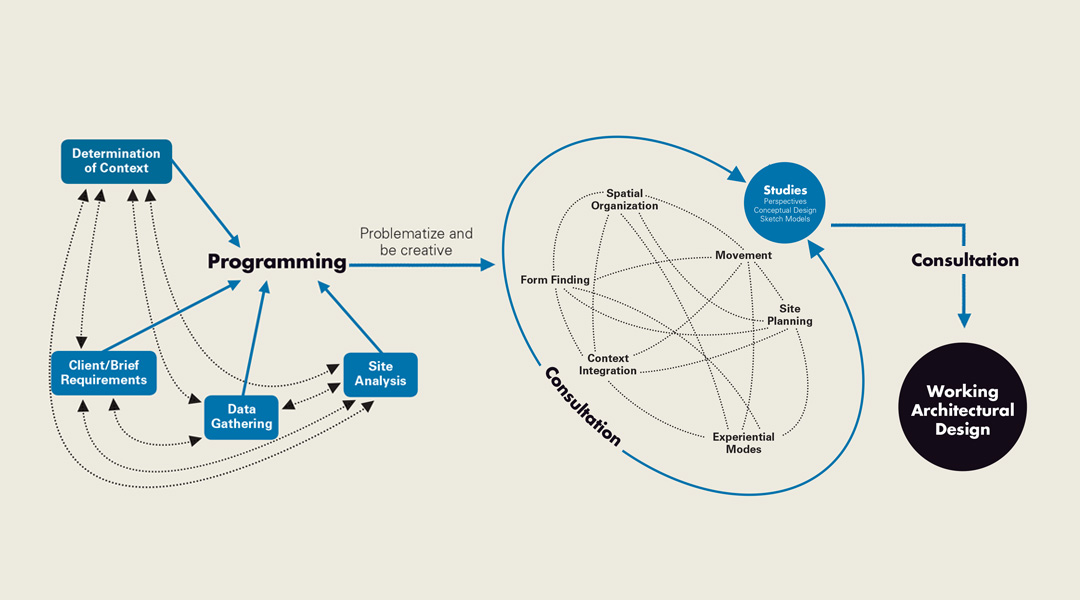

The presented diagram attempts to capture how critical thinking works in architectural design in our college. It is non-linear and highly iterative, with the student going back to repeat steps as needed, as we critique the student’s decisions along the way. Other modes of criticism are obviously valid (e.g. crit session, presentation to the panel, peer evaluation), but the dialogue between design student and design professor (i.e. consultations) is essential and comes first in design class. Not included in the infographic are the individual attributes of the design teacher and the design student: teaching style, learning style, inspirations, and philosophy, to name a few.

“We teach you to think. We teach you to think critically.” I was speaking before freshman potentials—both accepted and waitlisted—and their parents at our college open house, when one of the fathers asked me for my opinion on the perceived strengths of architecture schools in Metro Manila. While each school is strong in certain areas, he related that the UP College of Architecture is said to teach design that leads to the architecture of “the present.”

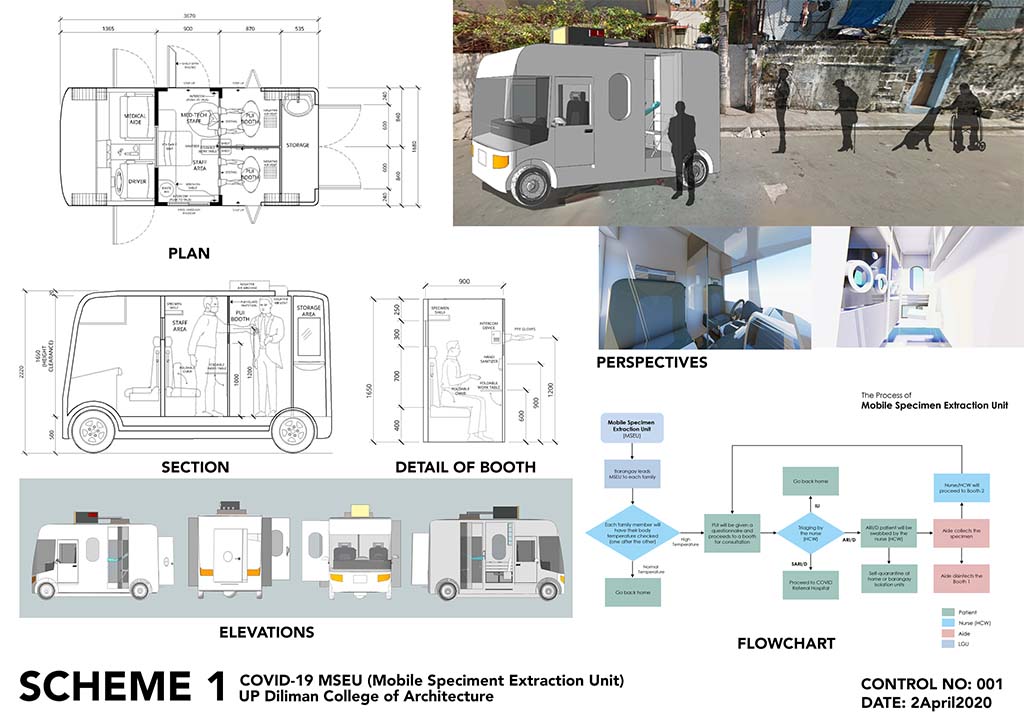

READ MORE: LOOK: UP architects design a COVID-19 testing vehicle

This is not untrue, but it isn’t the entire truth either. The ever-present complexities of context—economic, historical, social, political, environmental—provoke complex architectural problems. When UP Architecture students tackle these problems in a design studio, they are taught to run these complexities through a design process.

The design process, however, is not about finding permanent solutions, because constant fluidity is our reality, there can never be just one design response. Change comes from all quarters: the impact of natural disasters in the un-shaping of our cities, the insertion of technologies in buildings that predate them, and design trends that are at once fickle and relentless. American architect Peter Eisenman says that what architecture proposes are interpretations of the environment that are ‘problematized.’ Problematization, an important part of the design process, firstly requires understanding the world—the built and the natural, the tangible and the intangible. Organizing this information is the next task. Once organized, solvable and unsolvable problems are recognized. Through recognition, an architectural idea is introduced—an idea that undergoes permutation and iteration, builds upon itself, and continues to take shape. It becomes feasible through translation in form, space, and materials—architecture.

This process—the design process—is a messy task. With critical thinking, the messiness becomes comprehensible. With critical thinking, the individuality of designers emerges. How We Think (1910), a monograph by American philosopher and educational reformer John Dewey, documents one of the first definitions of critical thinking: “Active, persistent and careful consideration of any belief or supposed form of knowledge in the light of the grounds that support it, and the further conclusions to which it tends.” Without critical thinking—the conscious and voluntary effort to establish belief upon a firm basis of reasons—creativity in design is lost, and architecture is reduced to whim.

YOU MIGHT LIKE: PSID Exhibit 2019 revisits geometry lessons with HUGIS ATBP

To elicit critical thinking from students, Dewey’s two sub-processes can be applied. The first is establishing “a state of perplexity, hesitation, and doubt.” Steer the conversation towards the assessment of the design. Question the student’s train of thought that led to the design. Determine what basis began the train of thought in the first place. It doesn’t matter what the answer is—it can be as simple as compliance with building code, or as introspective as paying homage to the delights of a past experience. Allow the student to answer these questions.

The second sub-process is “an act of search or investigation directed toward bringing to light further facts…to corroborate or to nullify the suggested belief.” Challenge the student to find the rationale behind every design decision. The answer, “naisip ko lang,” is not critical thinking. If an acceptable reason cannot be found for a design decision by both teacher and student, an additional iteration in the design process has to be made.

READ MORE: Tan Tik Lam designs an enclosed yet open house in a compact Indonesian city

Guiding students in this manner gives them the opportunity to think critically for themselves. It must be done for every student in a design studio, no matter how large the class. It is exhausting. The spark of understanding does not always happen, but when it does, it is utterly fulfilling.

It is never boring to be a design teacher because responses to the design process yield great variety. Design is borne of past experience and prior knowledge, the sets of which are as many as there are individuals. The possibilities are multiplied further by the variations of creativity that occur during the design process. Acknowledging this variety redounds to acknowledging the individuality of the person who thinks critically and responds uniquely. Perhaps it is this process that makes people say that UP Architecture students are taught to design architecture of “the present.” But I daresay the process could very well yield designs that hark back to the past… or foretell the future.

YOU MIGHT LIKE: Professorial Typologies: The different professors you will meet in Architecture school

After the college open house, we had refreshments outside the amphitheater. Students, parents, and faculty were milling about on the grass, and the parent who asked me the question approached. We conversed amiably, the man sharing that he and his wife were keen to send their son to another architecture school, but their son was adamant to enter our college. The final decision will affect a young person’s life. Wherever he finally pursues his architecture studies, may critical thinking prevail.