Her modern mark: Rediscovering the life and works of design visionary Charlotte Perriand

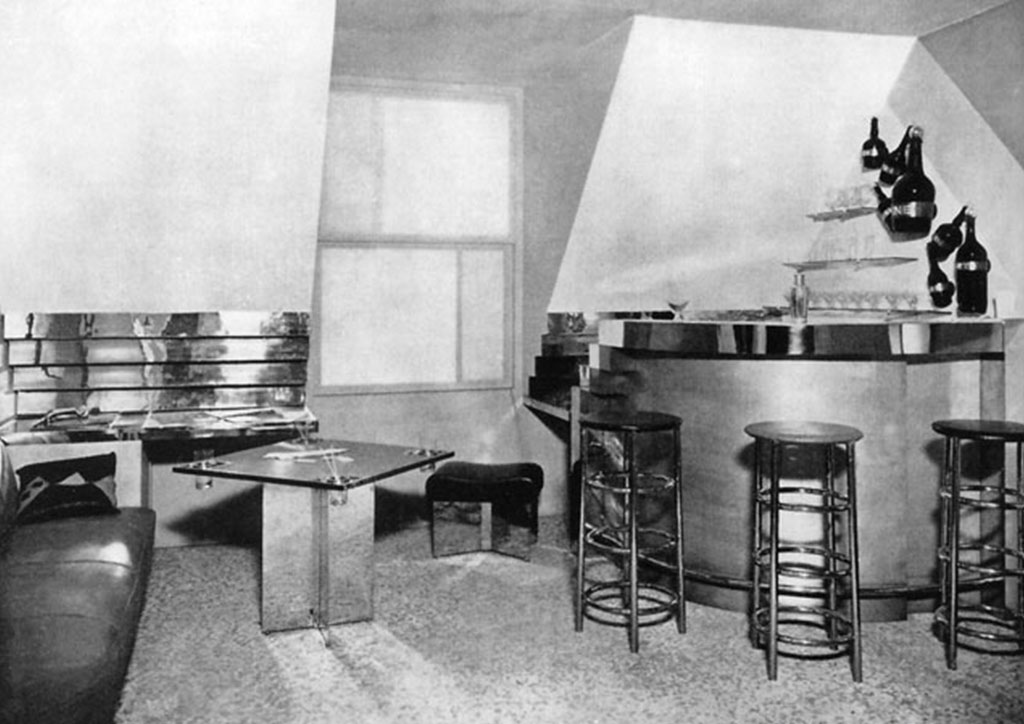

“The extension of the art of dwelling is the art of living — living in harmony with man’s deepest drives and with his adopted or fabricated environment,” writes Charlotte Perriand in her 1981 L’Art de Vivre article. Born to a tailor and a seamstress on October 24, 1903, Charlotte Perriand was introduced to the realm of design at an early age. Though she always embraced her present environment, Perriand’s creativity has always been imaginary, with her impressive drawing abilities noticed as early as high school. In 1920, her mother encouraged her to enroll at the École de L’Union Centrale des Arts Décoratifs (School of the Central Union of Decorative Arts), where she studied furniture design for five years. Two years after graduation, she applied for a job at Le Corbusier, where she encountered a rejection from the architect himself saying “we don’t embroider cushions here.” Determined to prove her capabilities, Perriand made a name for herself through her ‘Bar in the Attic’ installation, leading Corbusier to change his mind.

Originally designed for her rented apartment on Place Saint-Sulpice, the ‘Bar in the Attic’ installation was mainly composed of streamlined materials. Perriand arranged shiny-chromed stools; steel, zinc, and glass tables and countertops; and a built-in gramophone into a complete exhibit, forming an avant-garde exhibition. When Corbusier saw the installation, he contacted Charlotte Perriand himself. “I think the reason Le Corbusier took me on was because he thought I could carry through ideas; I was familiar with current technology, I knew how to use it and, what is more, I had ideas about the uses it could be put to,” recalled Perriand in an interview with The Architectural Review. Perriand collaborated with Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret and was in charge of interior work and design promotion.

Charlotte Perriand worked with Corbusier for a decade. Their projects blurred the lines between masculine and feminine design, something that wasn’t prevalent during their time. Perriand designed chairs using Corbusier’s principle of “a machine for sitting.” With her use of tubular steels for the chairs she crafted, Perriand was slowly discovered by many and was remembered as one of the very few designers who utilized the material. She then emerged from Corbusier’s shadow and worked with Jean Prouvé (8 April 1901 – 23 March 1984), a self-taught architect and designer who “introduced the machine age and industrial engineered modern design aesthetic to interiors in the steel, aluminum, and architecture he created.” Perriand joined Prouvé in designing screens and stair railings. Together they made a significant contribution during the second world war when Germany invaded France and the low lands, designing military barracks and furnishings for temporary housing.

In 1940, Charlotte Perriand parted ways with Prouve and left for Japan where she advised the government on raising the standards of design in the Japanese industry to develop products for the West. She experimented with local materials and textures such as bamboo, woven straw, fabric, lacquer, and pine, and explored traditional Japanese aesthetic codes, many of which bore parallels to her own Modernist leanings. The trip proved to be an influential experience in her career, seeing how she “infused her own designs with what she extolls as the virtues of an integrated approach—architecture-furniture-environment—creating a harmonious interior space.”

The Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor ruined Perriand’s plans of returning to France via America. Despite her being forced into Vietnamese exile, Perriand maximized her time by studying woodwork and weaving, also gaining influence from Eastern design. It was also during this time where she read The Book of Tea, which is said to have a major impact on her work. She referenced this book throughout her career, reflecting the idea of Teaism, which is “a cult founded on the adoration of the beautiful among the sordid facts of everyday existence.”

The design influence of Charlotte Perriand (was immortalized through her works, with various art and design exhibits alluding to her utilitarian style. On October 2, 2019, 22 days before her 20th death anniversary, the Louis Vitton Foundation opened “Charlotte Perriand: Inventing A New World“, a large scale exhibition dedicated to the French architect and designer. Recently, the international perfume brand Aesop introduced Rozu Eau du Parfum, a floral fragrance that pays homage to the Wabara garden rose that bears her name, with vibrant Shiso accords that reference her lifelong love of Japan, and the bracing alpine environments she loved to explore.

Information obtained from architecturaldigest, core77, and Louis Vitton Foundation.

READ MORE: Wonder Women: The 5 female Pritzker Prize Laureates since 1979