Name these 7 architects who started out as mentees

While some architects go solo from the get-go, others start their careers through mentorship. Training under architecture and design industry giants has its pros and cons. In the case of the architects featured here, their mentorship led them to develop styles that are either distinct from or influenced by their mentors and eventually led them to go side-by-side or face-to-face with their previous employers. Can you name the architects who first found mentorship and employment in the offices of these architecture legends?

1 Toyo Ito

This bespectacled female half of a world-renowned design duo from Japan was among a number of now-famous architects who were under the mentorship of 2013 Pritzker laureate Toyo Ito, where she worked for six years. Ito remembers this architect as his apprentice who cried a lot, that he admonished her about it in a group meeting in front of her peers. However, after starting her own practice in 1987, she blazed quite a trail, culminating with her winning the 1992 Young Architect of the Year award from the Japan Institute of Architects. In 1995, she established her now renowned architectural firm with an apprentice in her studio, and they gained acclaim for prestigious projects such as The New Museum in New York City, USA, and the Rolex Learning Center at EPFL in Lausanne, Switzerland (pictured). Interestingly, the design duo won the Pritzker Prize in 2010, three years earlier than their mentor.

YOU MIGHT LIKE: Wonder Women: The 5 female Pritzker Prize Laureates since 1979

2 Louis Khan

Before becoming a household name because of his collaboration with Richard Rogers for the Centre Pompidou at the age of 33, and eventually winning the Pritzker in 1998, this architect was in mentorship for a short time under the legendary Louis Kahn from 1968-69. He first met Kahn at the house of Robert Le Ricolais, a mutual friend and the professor of a class he attended at the University of Pennsylvania. Kahn invited him to his office one day where he eventually found employment, and he recalls working on a single project: a typewriter factory. Though our architect’s mentorship was brief, he had fond memories of Khan, whom he called the ‘little man who was so strong, so persistent, so devoted,’ in an interview for Surface magazine. As fate would have it, our architect found himself “face-to-face” with Kahn again when he was tasked to design an addition to the Kimbell Art Museum (pictured), which is right across the original 1972 masterpiece designed by his mentor.

READ MORE: Back To The Drawing Board: 10 Unbuilt projects by famous architects

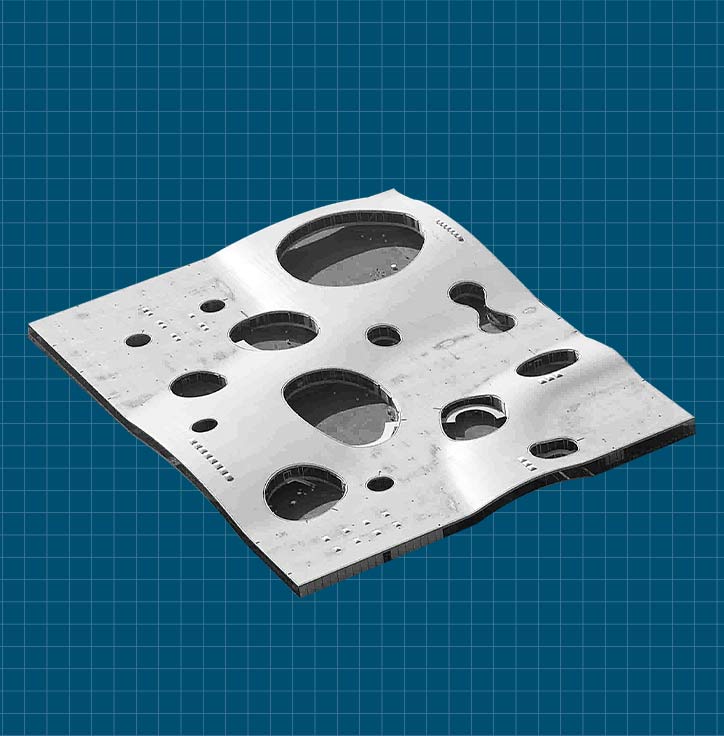

3 Kenzo Tange

This architect made news as a critic of Zaha Hadid’s winning entry for an Olympic Stadium for the Tokyo 2020 Olympics, voicing his fear that it is a white elephant waiting to happen. Already a prolific name in modern architecture, with offices under his name in China, Italy, and Spain, our Japanese architect first found mentorship and employment under the “Father of modern Japanese architecture,” Kenzo Tange. He was heavily influenced by the philosophy and ideals of his legendary mentor, which are reflected in his early work. Perhaps the most notable name to have worked in Tange’s studio (where he worked for a decade), our architect eventually started his own practice in 1963 and has since developed a more modernistic approach to his architecture, most evident in the Art Tower of Mito, an arts complex in Ibaraki, Japan (pictured).

YOU MIGHT LIKE: Here’s how 5 architects designed their first mark in architecture

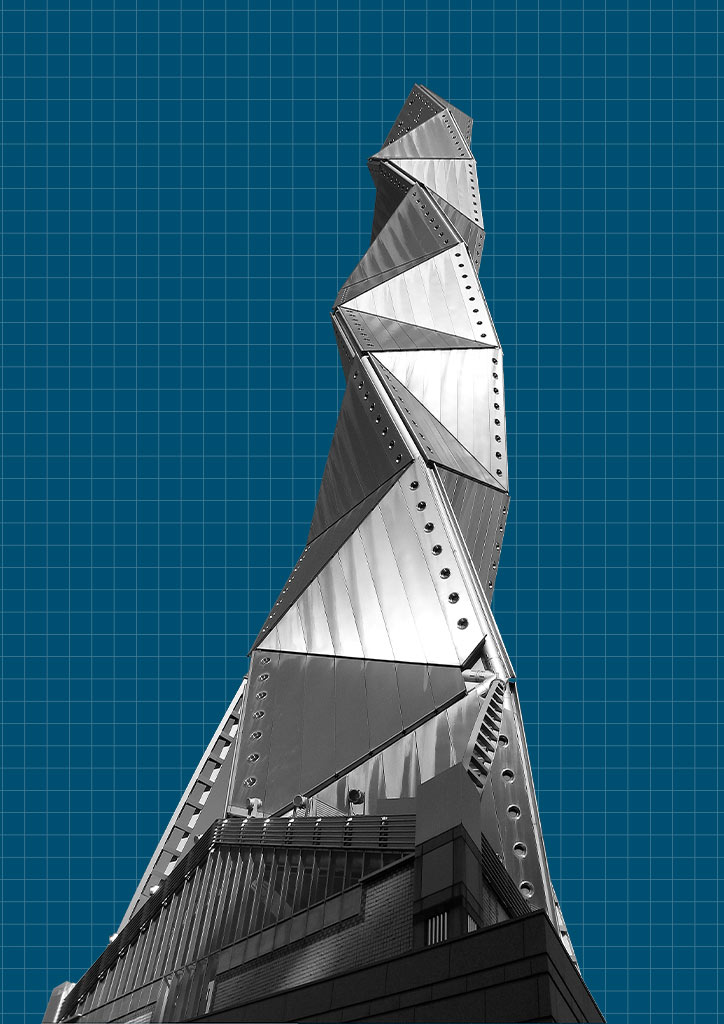

4 OMA

Credited with having successfully helmed the construction of the CCTV Headquarters Tower, that controversial Beijing landmark by OMA, our next architect finally decided that he has made a big enough name for himself, and broke away from the firm to establish his own practice in 2010. He was hardly the first of “architectural darlings” to have left OMA (helmed by the charismatic Rem Koolhaas), which has garnered a reputation as a nesting ground for some of today’s brightest architectural talents. He joins Bjarke Ingels of BIG fame, Julien de Smedt (JDS Architects) Winy Maas (MVRDV), and many others who are now enjoying success in their own practices after their mentorship at OMA. A former partner and director of OMA’s Beijing and Hong Kong offices, our architect was in charge of the Rotterdam-based firm’s Asian work, which includes the likes of the Maha Nakhon supertall in Bangkok, The Interlace residential complex in Singapore, and the Taipei Performing Arts Center in Taiwan. The design language he employed in his past firm—pixelated forms, cubes, and bold suspended volumes—is still present in his firm’s latest projects. As of writing, he was working on the Angkasa Raya (pictured), a mixed-use tower project for Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, directly across the iconic Petronas Twin Towers.

READ MORE: Green Screen: Proving eco-friendliness with these 5 structures

5 Zaha Hadid

“She wasn’t a good boss, but was a very good teacher,” says our next architect of his former mentor and employer Zaha Hadid, in an interview for designboom. Nevertheless, the sinuous curves and parametricism emblematic of Hadid’s work seem to have rubbed off on this architect. Born in Beijing in 1975, he received his masters in Architecture from Yale University, where he garnered attention for his Floating Islands project. During his one-year stint in Zaha Hadid Architects, he and his fellow apprentices had to learn quickly as the firm was bombarded by projects all happening simultaneously, an experience that proved useful when he started his own practice in 2004. His big break came when his firm won a 2006 competition to design the Absolute Towers (pictured), a pair of curvy twisting towers in Mississauga, Canada, eventually completed in 2012. This project gave him the distinction of being the first Chinese architect to snag a major international architectural commission, and it opened the floodgates to numerous other commissions, mostly in his native China.

YOU MIGHT LIKE: The Sensuous Heydar Aliyev Cultural Center by Zaha Hadid Architects

6 Ed Ledesma

Our next architect found public attention in 2011 for a pro-bono concept, which he did with furniture designers Budji Layug and Kenneth Cobonpue for the redesign of NAIA-1, then tagged as the World’s Worst Airport by a backpacking site. Before this concept went viral in social media sites, this architect began as a scholar in the Polytechnic University of the Philippines where he graduated with a degree in Architecture and found work in Leandro V. Locsin Partners later on. He stayed in the firm from 1997-2002, under the mentorship of managing partner Ed Ledesma. While he was working on a project in Bacolod, local furniture designer Budji Layug extended him an offer for a design partnership, which his mentor advised him to take. From then on, our architect has won numerous design commissions through this collaboration, with his reach extending to countries like Malaysia, France, and Israel. Pictured here is one of their projects, The Reef in Mactan, Cebu.

READ MORE: Punong: A nature-embraced family retreat by Ed Ledesma

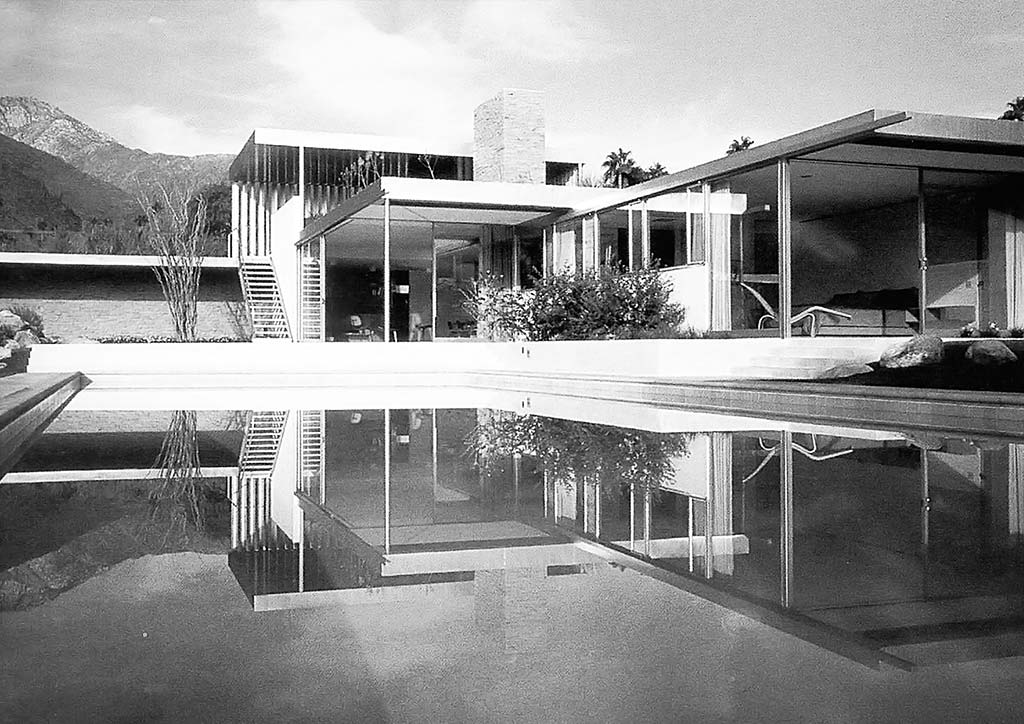

7 Frank Lloyd Wright

Before he found fame in the architecture world for his minimalist Modernist homes in Southern California (where he lived and built for the best part of his career), our often overlooked Austrian architect immigrated to the United States in 1923. He met his future employer, architecture icon Frank Lloyd Wright, in the funeral of another legend in architecture, Louis Sullivan, the ‘Father of the Skyscraper.’ Our architect was promptly hired in 1924 and put in charge of the Taliesin atelier while Wright was in Japan. This turned out to be a brief stint as work ran out in 1925 and he left Wisconsin for California, where he partnered with architect Rudolf Schindler before going out on his own. He found and developed his signature style which led to more than 300 house commissions, one of which is that of the Kaufmann Desert House (pictured). Built in 1946 for department store tycoon Edgar J. Kaufmann Sr. (who commissioned Wright to build Fallingwater), it is now considered by many architects and critics a masterpiece in the International Style, an architecturally noteworthy residence that is regarded with the same reverence reserved for iconic American homes such as Fallingwater, or the Gropius House.

YOU MIGHT LIKE: Behind the Anger: The mid-century modern Church of the Angry Christ

This first appeared in BluPrint Volume 4 2015. Edits were made for BluPrint online.

Sources: BluPrintImages from ArchDaily (Kimbell Art Museum); dac.dk (Rolex Learning Center); wikipedia.org; (Art Tower Mito); ideasgn.com (Angkasa Raya); commons.wikipedia.org (Absolute Towers); Budji+Royal