Did we even learn our design lessons after Typhoon Ondoy?

The country is still reeling from the effects of Typhoon Ondoy and Pepeng (this commentary was written in mid-October 2009). Flood waters still cover much of Manila’s low-lying areas, Laguna de Bay’s lakeshore and Central Luzon. The floods and landslides left hundreds dead, a million people displaced or affected and anywhere from 10-20 billion pesos in damage wrought.

The lessons learned from the disasters point to deficiencies in government preparedness and disaster management. These disasters also point to deficiencies in physical planning and design, which is within the purview of professionals in the fields of planning, architecture, urban design, landscape architecture, even industrial design. Nevertheless, the calamities mothered a slew of new inventions and design proposals—some serious but others that literally wouldn’t float.

Urban and Regional Planning

The cause of the disasters can be partly attributed to uncontrolled urbanization or the spreading of settlements into areas not compatible for intensive development. Urban and settlement patterns in the Philippines has erased or constantly come in conflict with natural processes and elements in the landscape like sensitive mountains and steep hillsides, rivers and its tributaries, and flood plains.

Planners in government have to set boundaries for allowable development. Planners for private developers should say no to developments that they, in their professional consciences and scientific study, know will lead to possible danger, long term disaster or long-term degradation of the environment.

The disasters in Metro Manila point to ill-designed subdivisions that have been built without proper drainage strategies or assessments of vulnerability. Subdivisions themselves perpetuate green field-consuming urban sprawl that reduces the ability of the landscape to absorb storm water. This leads to the overburdening of whatever drainage systems are in place.

The whole Environmental Impact Analysis and Clearance Certification process is a joke, a fill-in-the-blanks, one-size-fits-all document that does little to protect the environment. Most of these are submitted before the fact that the actual planning and detailed site design is completed, so how can impacts really be assessed?

Urban Design and Landscape Architecture

On the next level or scale down from regional and city planning we have urban design and landscape architecture. Here the problem is actually one of non-existence or extreme lack of any real urban design or landscape architectural input into how we shape our modern physical settings.

Few private and even fewer public projects benefit from the services of professionals in these two fields. Hence the veritable lack of well designed parks, open spaces and streetscape. In to these would have been incorporated interventions that would mitigate the effects of storm water, pollution and the problems attendant to high-density life in our cities and suburbs.

Less and less open and green space is given to commercial and residential developments. More and more paved surfaces channel storm water into drains. There is a move to replace roofs with ‘green roofs’ and this is a welcome movement but it may be a matter of too little too late in Metro Manila.

Public parks are absent from our towns and cities. Public clients in the few projects offered to professional landscape architects expect central parks to emerge from 300-square-meter plots left over from roads.

Even more worrying is the reduction of whatever open spaces in municipal and city plazas and government complexes. These are replaced with basketball courts, kiosks, extension offices or other facilities each new administration feels the need to build.

Architecture

In the aftermath of the disasters many suggested that the Philippines needed a new type of house. Floating houses of ferro-cement (a lightweight concrete invented a century ago in Europe) were mulled for those areas that were flood prone. The elevation of structures on piloti was also suggested. This mimicked traditional architecture of nipa huts, which would have been a more practical alternative, save for the fact that bamboo is hard to find in sufficient quantities.

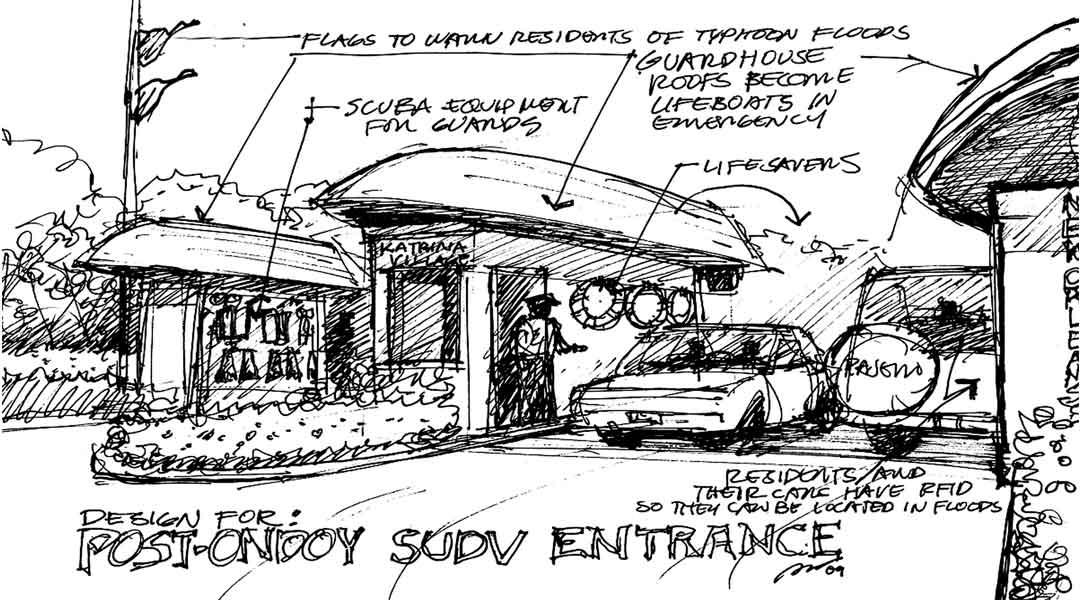

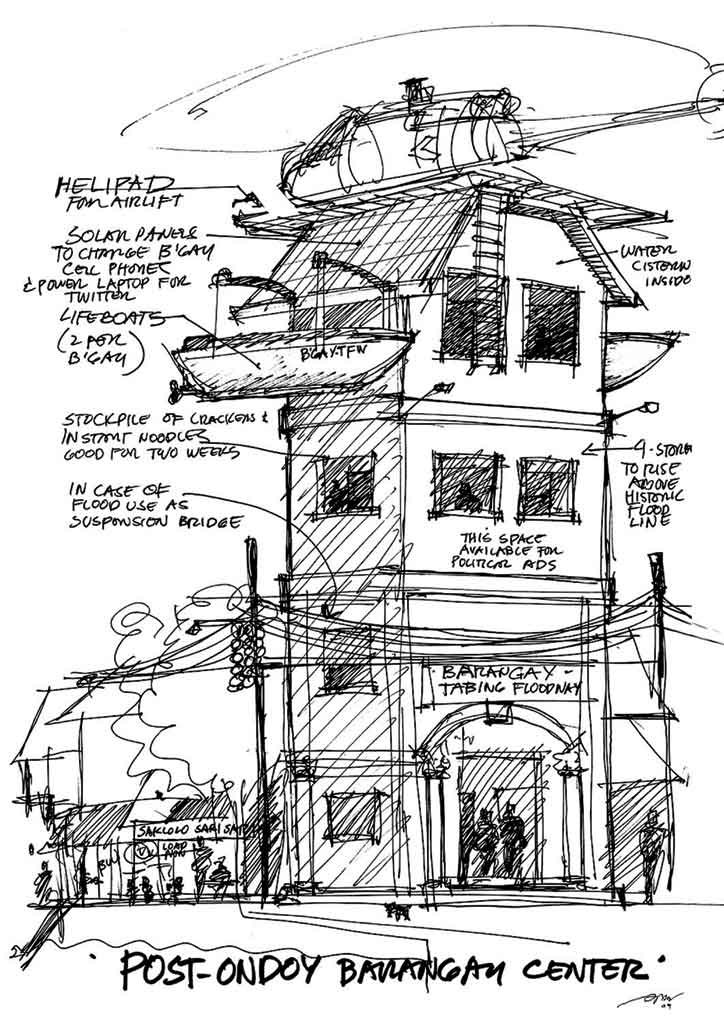

Also suggested were new designs for barangay centers with lifeboats and a helipad. The structures were to be four storeys or at least a storey above the historical flood level high in the area it was to be built. An option too for entrances for gated communities was put forward. Lifeboats were used as roofs for guardhouses, which would shed them for use when needed. Scuba gear and lifesavers were to be hung from the walls making them easily accessible for use.

On the serious side, there were calls to ban basements altogether. Residences in dangerous areas were proposed to have upper decks again way above the historical flood level highs. Emergency provisions were to be permanently stored in the upper levels.

There was however not much any new design for architecture could do when faced with relentless rain, the force of rivers and cataclysmic persuasion of landslides and flood surges to sweep away everything in its path.

Industrial Design

At the smallest scale there were calls to invent a salva-kotse, a device to strap on one’s car to save it from the rising tide of mayhem and destruction. Personal protection and safety could be ensured too with compact inflatable life vests built into parkas of adults or backpacks of children. RFIDs (radio frequency identification devices) now seem to be considered as a requirement making rescue, relief or identification (if recovered) easier for everybody or every body.

Another industrial design suggestion is for super–large zip-lock bags. These were to be made large enough to put whole household appliances in to waterproof them. A special zip-lock could be made for computers and other media gadgets (actually already available for those going to the beach). The additional improvement was that all these could have cable eyes to be able to string the entire lot so your worldly possessions would not float away.

Calls should be put in for cell phones with ultra long battery lives or one with an emergency beacon that would automatically beep a signal for three continuous days, again to help in rescue or recovery. Another necessity for those stranded was for drinking water and a suggestion was made for a collapsible filter embedded again in one’s parka or backpack that could filter and store water scooped up from flood.

READ MORE: The good, the bad, and the ungainly: An urbanist reveals the importance of scale in Makati

Design can save. Architects and allied professionals can apply their creative talents to provide solutions for people, communities and cities put in harm’s way. Design, however, would make its best and most sustainable impact if applied to prevent disaster way before it rears its ugly face.

We should build our cities and settlements in hazard-free areas, we should design with nature not against it. We should create architecture that treads lightly on the land, and made with materials also meant to cause the least trauma on resources. We should recover our forests, parks and open spaces, create gardens that soak rainwater and help cleanse what runs off to our rivers and seas.

We should ultimately design our lives with more sensitivity to the fragility of our environment, an awareness that everything we do to our surroundings has repercussions that can last for centuries and an appreciation that if we continue with our current ways we can only count on disaster to visit us with alarming frequency. ![]()

This article first appeared in BluPrint Volume 8 2009. Edits were made for Bluprint online.

Illustrations by Paulo Alcazaren