Making an Architect, Testing an Architect

Architectural problems are solved in a sequential path meandering from the creatively schematic to the technically specific. The making of an architect follows a similar trajectory—with rung after rung to be climbed; from design and history to theory and practice, all to be mastered in time. But not at the same time! Architects blossom in the context of a slow and methodical process, a gathering of diverse intelligence that permit the opening of doors of a life rich in capabilities, whether or not one elects to work in the field. To apply—simultaneously—the principles of art, science and philosophy promises to enliven one’s time on earth.

School is where design thinking should be reinforced at every opportunity—even in contexts far removed from the core. Consider as an extreme example the obligatory general education course on Rizal. A tired reading of the Noli focuses onlyon his political dialogue. A more pertinent approach for design students considers how Rizal appropriates the built environment as a medium upon which to project social commentary. Indeed, on the very first page of the Noli, his character, Captain Tiago, is found planning a party at his home located upon the Binondo creek “…which plays, like many rivers in Manila, the multiple roles of bathhouse, sewer, laundry, fishing hole, thoroughfare and even drinking water…” By page two, we hear the narrator mock the house, which is “…somewhat squat, its lines fairly uneven. Whether the architect who built it could not see very well or this resulted from earthquakes or typhoons, no one can say for sure.” Soon enough, we are transported to the second storey: “…finding ourselves in a broad expanse called the caida…which tonight will serve both as a dining and music room. In the middle, a long table, abundantly and luxuriously appointed, seems to wink sweet promise at the freeloader…” From these passages, and others like them, students recognize how effectively social and political ideas can be enriched with allusions to physical context. By approaching Rizal from this new perspective, design students will not only be more inclined to appreciate his message, but will also confirm that narrative is foundational to design. Similar pedagogic gymnastics can make every course engaging, even inspirational to the design student.

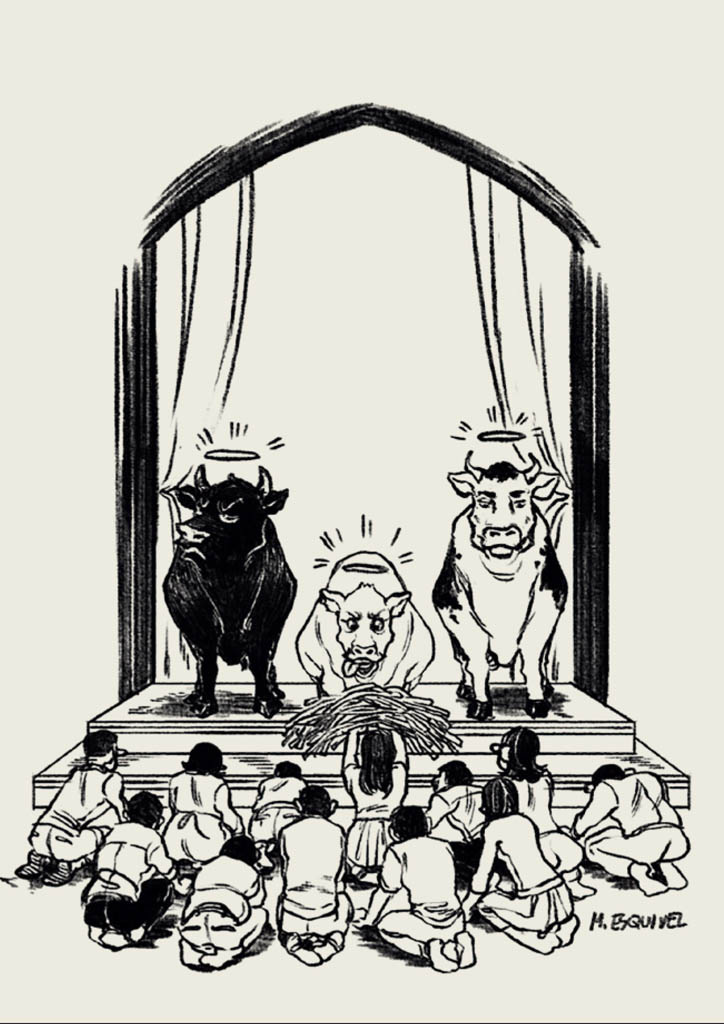

Slay the sacred cows

Academia is, or should be, a protected universe—a space for students to question everything about the imperfect world bequeathed their generation. If only educators adopted a similarly necessary skepticism regarding the systems and traditions deployed in the monumental task of molding architects. Shouldn’t the institutions of school and government come together to reinvent practice, regulation and tradition to face imminent challenges? Design is undergoing a global revolution, an immediate manifestation of which will be the diminished protection offered by national borders. In the past, Philippine architects worked behind a moat where they were only responsible for meeting local benchmarks of competence and experience. That moat will soon be breached as ASEAN nations, and then the world, flood in. The only possible defense will be peerless education, an effective (and perhaps longer) internship, a more pertinent testing regime, and a reevaluation of the entire regulatory structure of architecture and construction.

That schools are tied to a universally mandated curriculum leaves unearthed alternative methodologies, approaches and priorities. Has this helped the Philippines? Has our infrastructure produced an enviable constellation of the best designers in the world—as we have every right to expect? Do we dominate international competitions? Do we regularly snare plum commissions within the global marketplace? If yes, then let us leave the system as is, intact and unchanged. If not, then perhaps innovation may be the only way to enhance outcomes for the benefit of the nation. Competing for the dubious honor of producing ‘top notchers’ is not enough.

Less crowded design studios

Given the self-evident centrality of design studio within architectural education, reform should logically begin there, and every program should consider redoubling its commitment to an enhanced design studio experience. One of the most impactful changes possible is guaranteeing an uncrowded learning environment. The current practice of cramming 30 or more people into a design class degrades a teacher’s capacity to meaningfully interact with students. In my more than 25 years of teaching architecture and interior design, I have found it quite impossible to offer consistent, meaningful critique to more than 15 students. No two students have analogous capabilities, and thus no single teaching method is universally effective. Certainly, a more personalized approach is costly, yet without imposing strict limits on studio size, we fatally impair the ability to teach and learn design.

Homework

I would also suggest a radical reconsideration of how class time is deployed. The design studio is only valuable as a venue for teaching what design is, how design is developed, how design is understood and how design is critiqued—subjects mastered only via extensive practice and interaction. Design work itself should only be performed at home to free up class time for the higher value activities enumerated above. International pedagogic norms dictate students should minimally spend 2-3 hours on homework for every hour spent in class. This output should form the basis upon which class time is structured.

Learner-centered teaching

It is likewise important for each teacher to adopt an instructional method sufficiently flexible as to accommodate various learning styles. Growth comes from different places, at different rates, for different people. Some students are too shy to offer critique. Give them additional assistance in that area. Others develop solutions without exhausting thematic possibilities. Encourage them to be more thoughtful and patient during the conceptual phase. Designer teachers are effective when they are flexible and compassionate, promoting strengths and mitigating weaknesses of individual students.

YOU MIGHT LIKE: Lessons from Anthology: Never forget the basics of architecture

No to group projects

Lastly, and perhaps most significantly, we must eliminate the ultimate corruption infecting our design studios—the group project. The very idea of communal creativity is a contradiction in terms. Can one imagine artists sharing a canvas? Matisse on the left and Degas on the right? When considering the absurdity of that vision, the responsibility of design schools to every student becomes clear, especially when supported by the regulatory admonition in Republic Act 9266 that entry to the practice of architecture is “determined upon the basis of individual personal qualifications.”

Loosen CHED constraints

The State has stipulated an interest in the education of the architect in order to promote a safe, pleasant and productive framework within which our lives unfold. How do we know this? The architecture curriculum stipulated by the Commission on Higher Education Memorandum 61 powerfully infers this objective. Under the section titled “Policies, Standards; and Guidelines for the Bachelor of Science in Architecture,” design is identified as a cultural resource. Schools are unambiguously commanded to direct “the thrust of architecture education to the needs and demands of society and its integration into the social, economic, cultural and environmental aspects of nation building.

CHED further defines the architect as a person who “is responsible for advocating fair and sustainable development, welfare and cultural expression of society’s habitat in terms of space, forms and historical contexts.” In light of this directive, and the fact that schools are not autonomous with respect to the architecture curriculum, the educational establishment might profitably lobby for looser guidelines so that schools may create their own curricula to promote a diversity of approaches to architectural education. Progressive building codes in some countries encourage a more liberal, performance-based alternative to the rigidly prescriptive tradition we are familiar with. Why not similarly provide space for innovation in design education?

Board exam

Some suggest that design skills are impossible to verify, and point to the deletion of the design section in the licensing exam as proof. How can we submit our students to ten grueling semesters of design studies and then suggest that which they learned cannot be evaluated? The State is on record in supporting design values through legislation. In fact, the preamble to Republic Act 10557 clearly states: “It is the declared policy of the State to enhance the competitiveness and innovation of Philippine products, create market-responsive design services, while advocating economic and environmental sustainability. The State shall also endeavor to promote an economy and society driven by design and creativity responsive to our fast-changing times and reflective of the Filipino culture and identity.”It could therefore be argued that design, because it is central to the needs of the nation, should be of sufficient importance to be returned to the architect’s licensing examination. The final threshold a prospective architect must pass should be a vehicle with the capacity to demonstrate a baseline of competence and proficiency. Can it provide an accurate assessment of knowledge, experience, capability and discernment, an effective distillation of years of training? Given the ubiquity of this kind of exam around the world the answer seems to be yes.

Yet the preparatory industries which have sprung up in support of the board candidates suggest a gap between that which they know and that which they will be tested on. If true, that a uniquely presented set of concepts and principles are served up during this exercise, then perhaps the exertions necessary for success should be considered as the basis for a third body of knowledge (the first two being 5 years of school and 2 years of apprenticeship) supported by a mandated addendum to the academic curriculum. In other words, if the typical eligible candidate cannot expect to pass the board exam without additional preparatory classroom work, then is it not reasonable to expect either schools or government to offer such support as part of their mandate for education and oversight?

This article first appeared in BluPrint Special Issue 2 2015. Edits were made for BluPrint online.

READ MORE: A manifesto for architecture education in the 21st century