Name the architects behind these once-reviled, now loved landmarks

Criticism is not something new to the architecture and design industry. Even in history, several buildings and monuments have received both positive and negative feedback be it in terms of their form or function. Here are seven of the world’s most beloved landmarks that were once-reviled. Can you name the architects behind them?

01 Pyramide de Louvre

Proof that Parisians can be quite critical with their public landmarks, especially when they involved having their taxes raised, our first entry was a grand project of French President Francois Mitterrand who commissioned this architect to design a new entrance for The Louvre. While it did reduce foot traffic volume from the original entrance and save the historic structure from architectural stress, the new entrance, resembling a gigantic glass pyramid, drew the ire of many Parisians who felt it clashed with the museum’s classical architecture. Mitterrand’s personal interest in the procurement of materials is said to puzzle even the architect. Rumors have it that the new structure, as per Mitterrand’s request, was constructed with 666 glass panes in reference to the devil. These stories resurfaced in Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code. Nevertheless, like its fellow Parisian landmark, the Eiffel Tower, the Pyramide du Louvre eventually found its way to the hearts of local and international visitors alike.

02 Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

It is rather telling when a museum’s gift shop sells more postcards of the museum’s architecture than any of the artworks inside, as is the case of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Although considered an icon now, it wasn’t universally accepted during its construction. The museum is the swan song of our next architect, who died six months before it opened in October 1959. He found inspiration from his client’s collection of abstract art by Wassily Kandinsky, and the form of the nautilus shell. Initially derided by many critics as out of context, indulgent and an impractical exercise of form over function, the construction of the Guggenheim didn’t start until 1956, almost ten years after the death of its patron, Solomon Guggenheim. However, when the museum finally opened, critics turned silent. While the building did end up being difficult in accommodating artworks (imagine hanging paintings on tilted walls and dealing with spiraling ramps), it nonetheless succeeded in creating an iconic and memorable home for his client’s art collection, a building that is in itself an artwork to be experienced.

03 Eiffel Tower

Our next entry is a familiar story even to those who have the least interest in architectural history. Built as the centerpiece of the 1889 Paris Exposition Universelle, the Eiffel Tower was met with outcry even before its foundations were laid, from Parisians concerned about design and safety issues posed by the tower’s size. These fears proved to be unfounded with construction completed in two years, resulting in only one construction-related death. Engineer Gustave Eiffel eventually won the hearts (and wallets, being the tower’s initial operator) of the Parisian public and most of his detractors. Tour Eiffel has become symbolic of France, so much that when President de Gaulle proposed to dismantle and lend the tower to Montreal ‘67 Expo, it was unanimously rejected. During the German occupation, Hitler was not able to mount the tower, with lifts disabled by feisty Parisians, prompting locals to proclaim with pride that, “Hitler may have conquered France, but not the Eiffel Tower.”

04 Dancing House

Affectionately called “Fred and Ginger” by its co-architect after dancing duo Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers, the Dancing House in Prague is a sight to behold, with its deconstructivist form of glass and stone. The project was supported by Czech President Vaclav Havel, who once lived near the site; and sponsored by the Dutch insurance company Nationale-Nederlanden, which wanted a landmark building close to the riverfront. Our Croatian-Czech co-architect and his American collaborator came up with a whimsical design elaboration of yin and yang; a building composed of static yet seemingly in motion elements locked in dance—a visual metaphor of the state’s transformation from communism to democracy. The project was initially met with dismay from locals who feared the destruction of the place’s historical fabric, but they were eventually swayed by the president’s support of the project and the design pedigrees of our two architects. Today, the Dancing House is beloved by locals and camera-toting tourists, with the Czech National Bank issuing a gold 2000 Czech koruna coin featuring the building.

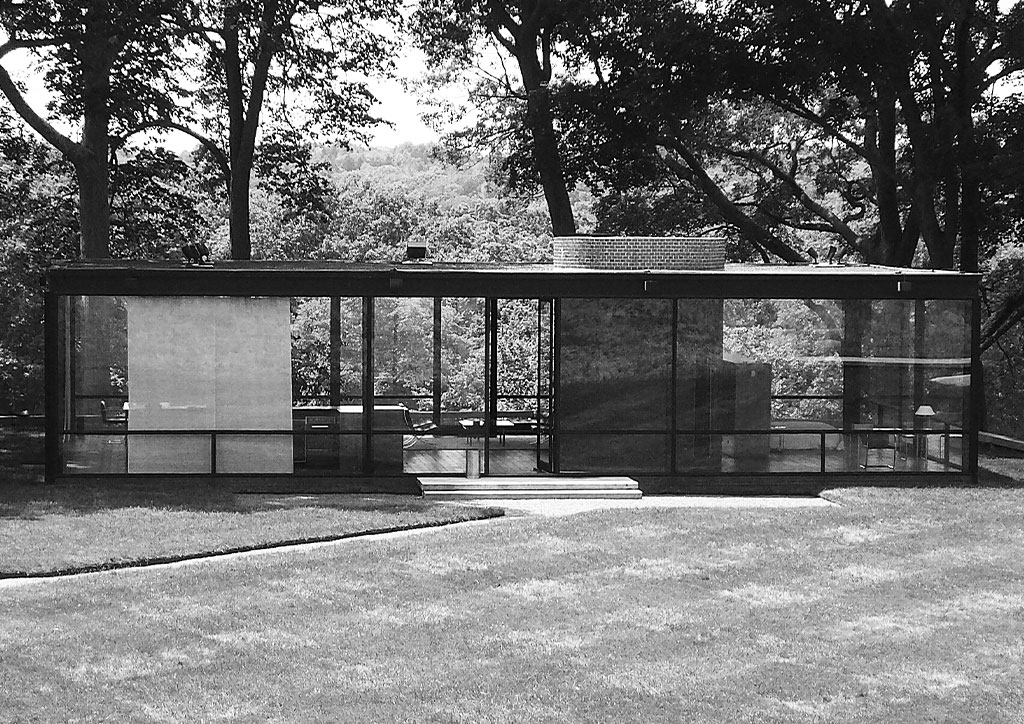

05 Glass House

Inspired by the concept of Glasarchitektur advanced by a group of German architects in the 1920s, the Glass House designed and owned by our next architect courted a lot of controversies. At first glance, it looks like a literal clone of Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House. This upset Mies as the Farnsworth House was actually designed first but built last. The Glass House was considered an “anomaly” amongst its colonial-style neighbors by those who wanted to preserve the town’s historic fabric. It features an expansive glazing and narrow steel supports housing one room, which opens on all sides to panoramic views of the expansive property. In fact, the only enclosed space was the bathroom, wrapped around by a cylindrical brick wall. It attracted unwarranted public attention during construction, causing traffic congestions in the small town and prompting the intervention of local police. Even after construction, policemen had to guard the house from trespassers. Our architect eventually opened his house for public tours on select days. From the small town nuisance it once was, to an architectural must-visit, the Glass House is now considered one of architecture’s modern masterpieces.

06 Washington Monument

What many consider an iconic monument to America’s Founding Father was once seen as “an asparagus,” by its own architect no less. Though this oversized obelisk looks simple to construct, the Washington Monument actually took 30 years to complete and involved a century of planning hampered by the Civil War, lack of funding and uncertainty about the merits of the chosen design. The product was a far cry from the original Greco-Roman temple-inspired design of its architect. The grand colonnade that was to encircle the present-day obelisk was omitted to reduce costs, prompting detractors to point out how bare it looked. The New York Tribune even called it “the big furnace chimney on the Potomac Flats,” a sentiment its architect shared. However, the snail’s pace construction of the monument dampened initial public criticisms, with changing tastes adapting better to the modified obelisk that incorporates the classical proportions of the Egyptian original. In 1888, the monument opened to the public with acclaim, even holding the title of world’s tallest structure before being eclipsed by the Eiffel Tower in 1889.

07 Sagrada Familia

Already a popular landmark even in its unfinished state, the Sagrada Familia’s unique architecture has long elicited polarizing reactions from locals and visitors alike since its groundbreaking in 1882. Our architect dedicated his final years working with almost feverish madness to perfect his basilica with his unique brand of Catalan Modernism architecture. He suspected that he’ll never live to see the completion of his masterpiece as it relied only on private donations, thus the slow pace of construction. True enough, the church was only 25% complete when the architect died in 1926. By then, the Sagrada Familia has ingrained itself deep into Barcelona’s social fabric. Issues such as the basilica’s design, the faithfulness of the succeeding architects to its original architect’s intentions, and whether this minor basilica would eclipse the status of the city’s cathedral, had been bones of contention among the city’s residents. Today, with advanced technology and tourism revenues, Sagrada Familia’s construction is picking up and is expected to be completed between 2026 to 2028.