Blood, sweat, and dreams: The Palacio de Arzobispado de Nueva Segovia

When Fray Miguel García San Esteban took over the Diocese of Nueva Segovia in Vigan City in 1768, he was young and eager to begin two important projects that he had been contemplating since his nomination as bishop two years before.

Established in 1595, the Diocese of Nueva Segovia was 173 years old. For 163 years, however, its official seat had been in Lallo, Cagayan—a regrettable choice, for the site was constantly flooded and beset with malaria. So for most of its existence, the bishops of the diocese chose instead to stay in nearby prosperous and cosmopolitan Vigan City. Finally, one of the bishops tired of the absurd situation and sent a request to the Vatican for the transfer of the diocese to Vigan. The request was granted in 1758.

It had been ten years since the diocese had officially been transferred to Vigan, but still, there was no proper palacio for the bishop; and the church in Vigan, erected by Juan de Salcedo in 1574, was little more than a parish church.

What the diocese needed, 41-year old Obispo Miguel García San Esteban reasoned in a letter to King Charles III, was a palace and cathedral that would reflect the glory of His Majesty, the magnificence of Spain, and the power of the Holy Roman Catholic Church. The successful, albeit short-lived, conquest of Manila by the British in 1762 had inspired numerous revolts against Mother Spain in the Philippine countryside. Although Spanish forces had successfully quashed the rebellions, it would do well to stamp out any remaining libertarian fire amongst the natives. Therefore, it was vital to pursue the construction and reconstruction of awe-inspiring symbols of Spanish supremacy with renewed vigor. It was especially important to do so in Vigan, for not only was it the third most important city of the islands (after Manila and Cebu), it was also here that one of the most bloody, obstinate and worrisome insurrections took place, led by Diego Silang in 1762-63, which hounded and nearly cost the life of Bishop San Esteban’s predecessor, Bishop Bernardo de Ustariz.

READ MORE: What was Vigan like before the UNESCO Heritage fame?

The Revolt of Diego Silang

Diego Silang y Andaya had been educated and made an acolyte by one of the priests in Vigan, and employed as a letter carrier for Spanish authorities. On his trips to and from Manila and around the countryside, the charismatic messenger spoke against abuses by Spanish officials, advocated self-governance and argued that Filipinos should be trained to take over leadership positions in the Church.

When the British invaded Manila on September 1762, Silang saw an opportunity to demand redress from the beleaguered Spanish authorities for the abuses of their officials in Ilocos. In exchange for his allegiance, Silang audaciously demanded the dismissal of the corrupt alcalde mayor, the abolition of tribute and forced labor, and his appointment as head of the Filipino army against the British forces. The Spanish administrators in Manila, however, had transferred judicial and other powers to Bishop Ustariz in Vigan City, who dismissed Silang’s demands and had him thrown in jail.

READ MORE: Miagao Church’s naked coralline limestone, a mistake for authenticity

Through the mediation of influential patrons, Silang was released. Silang, who had amassed thousands of followers, attacked Vigan to expel Spanish officials from the city. Ustariz and his priests fled to a convent in the town of Bantay, while the alcalde mayor and other Spanish officials fled to other towns. After successfully occupying Vigan and neighboring towns, Silang proclaimed Ilocos a free and independent state on December 14, 1762. The freedom lasted only six months, however. While in captivity, Ustariz plotted Silang’s assassination; and on May 28, 1763, Miguel Vicos, a friend of Silang, shot him in the back.

Bishop-Governor Ustariz

As Ustariz had predicted, Silang’s death deflated the revolutionary movement in Ilocos. Two weeks after the assassination, he received a letter from the Spanish lieutenant governor, Don Simon de Anda y Salazar, thanking him for “the victory over the insurgent Silang,” and promising a fitting reward for Vicos. More importantly, the letter confirmed that Ustariz would maintain “charge of the civil affairs of the province.” In addition, he was to take the arms confiscated from the insurgents and distribute these among loyalists so that they might defend the city from further attacks by rebel holdouts.

What Ustariz had not predicted was the nerve and tenacity of Silang’s widow, Gabriela. La Generala had mustered 2000 of her husband’s freedom fighters and led them on offensives to recapture Vigan City. Ustariz’s troops, however, outnumbered hers three to one. The Spanish had recruited Filipino soldiers from other regions, mostly Tagalog and Kapampangan, to fight the Ilocano rebels—it was divide et impera at its finest. Fighting muskets and artillery with bows and arrows and axes, Gabriela’s attempts to take the city suffered a crushing defeat. She and 80 of her men were captured. Her comrades were executed one by one; their bodies displayed in gallows in coastal towns as a warning to all who would oppose Madre España. Ustariz saved Gabriela for last. She was executed by hanging in the plaza in front of Vigan Church amidst chants of “Viva España!” It was a festive day, September 29, 1763—the feast day of the archangels Michael, Raphael, and Gabriel.

Bishop Ustariz had proven himself a strong and decisive overseer of the province, and there were clear signals that he would soon be elevated to Archbishop to replace the frail and weak-spirited Archbishop of Manila, Manuel Antonio de Rojo. Rojo died in January the following year, but Ustariz would not attain the exalted position that was within his grasp, for he died within months of his superior’s passing, in August of 1764.

READ MORE: Tunnel Vision: Fort Bonfacio War Tunnel Restoration

Arzobispado de Nueva Segovia

Obispo Miguel Garcia San Esteban would hold his post for 11 years, but he would not witness the erection of the grand cathedral that he had envisioned for his diocese. The construction of St. Paul Cathedral would not begin until 1790, eleven years after his death. He did, however, begin building a residence fit for an archbishop, with a proper ecclesiastical court and throne room—the Palacio del Arzobispado—but he would not live to see its completion in 1783.

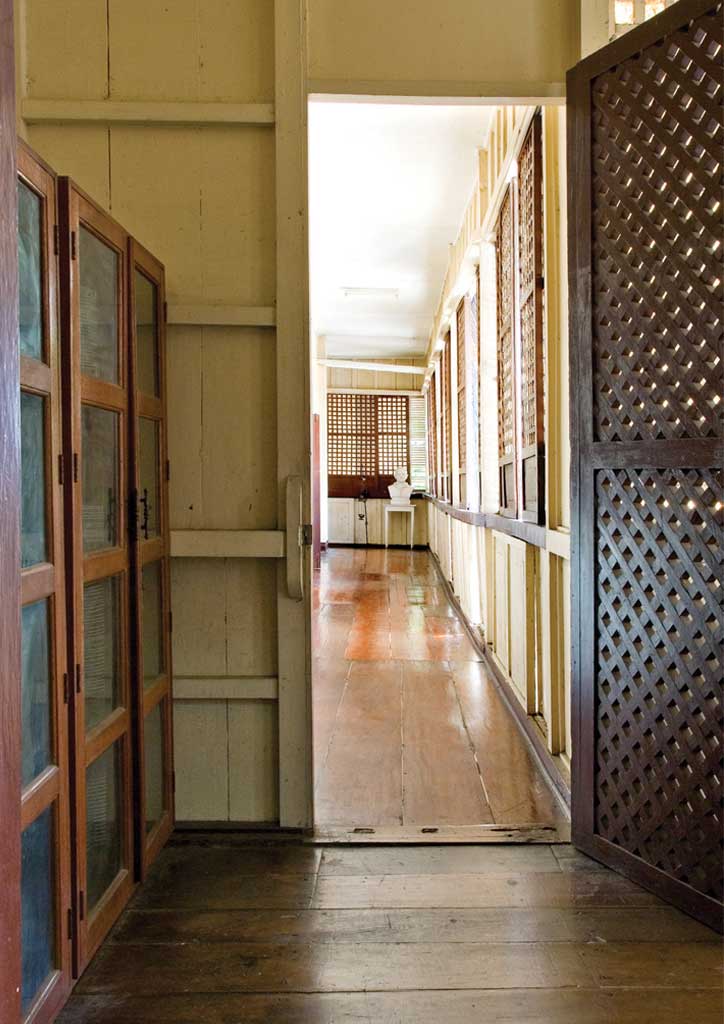

The palace flanks Plaza Salcedo, where Gabriela Silang climbed the steps of the scaffold to meet her death before a jeering crowd. The oversized bahay na bato, built with huge stones on the ground floor, sliding capiz shell windows on the second floor, and a massive, high-pitched roof, took seven years to build using forced labor. It was the largest structure in the city at the time, with three to four-foot thick ground floor walls built to ensure the safety of its occupants against attack. However, precisely because of its size and fortification, the palacio would be captured and taken over by different forces in the course of history: by the Katipuneros in 1896; by General Emilio Aguinaldo in 1898 and General Tinio in 1899, who used it as their headquarters; and by the Americans in 1900 and the Japanese in 1942, who used it as their barracks.

The palacio is the only surviving 18th-century arzobispado in the country. It is still the official residence of Nueva Segovia’s archbishop, but we are told that his private quarters are housed outside of the 227-year old building. The Museo Nueva Segovia houses the throne room, which is no longer used, and archdiocesan archives. Apart from the museum with its display of ecclesiastical artifacts from various churches in Ilocos Sur, and the grand scale of the building itself, there are few vestiges of the awe-inspiring magnificence of Spain and her powerful prelates.

Today, one would not readily imagine that this sacred (and comparatively bland) structure had been built on the blood, sweat, and dreams of people who shaped the history of the Philippines; or that time and again it had been employed for the bloody and profane purposes of war.![]()

This article was first published in BluPrint Volume 1 2011. Edits were made for BluPrint online.

Phtoographed by Ulysses Galgo

READ MORE: A Fitting Retrofit: The Restoration of Manila Cathedral