Stories in Stone: The cultural legacy of Manila’s oldest cemeteries

Manila’s oldest active cemeteries, Chinese and La Loma, have valiantly and stubbornly stood the test of time, from their first inception as Spanish-era burial grounds to their current evolution. Walking the streets and alleys of these spaces, one can feel the narrative; these turning paths speak volumes of what they have been witness to—from elaborate funeral services to wartime atrocities, to annual family celebrations during All Saints Day.

These spaces are vital elements of cultural heritage and represent important social, historic, architectural, and genealogical artifacts. In addition to their historic value, these cultural landscapes also meet contemporary needs for the living—to visit and remember those buried there, connect with cultural history, and experience a historic landscape.

La Loma Cemetery

During the early Spanish period, the dead were interred within or outside of churches. Coinciding with changing attitudes about burial in America and Europe, the colonial government, in the early 19th century, forbade the old practice of interring the dead in churches. Eventually, all towns under Spanish rule had a designated cemetery. The Catholic Cementerio de Binondo was located approximately three kilometers from Binondo in the hilly area of La Loma, which was then part of the arrabal of Santa Cruz.

The Binondo Catholic Cemetery was surrounded by a three-meter high stone masonry fence. A wrought-iron grill gate and a funeral chapel, distinctive for its dome and adobe walls, completed the design. The cemetery survives to this day as the La Loma Cemetery as does its chapel, under the care of the Archdiocese of Manila.

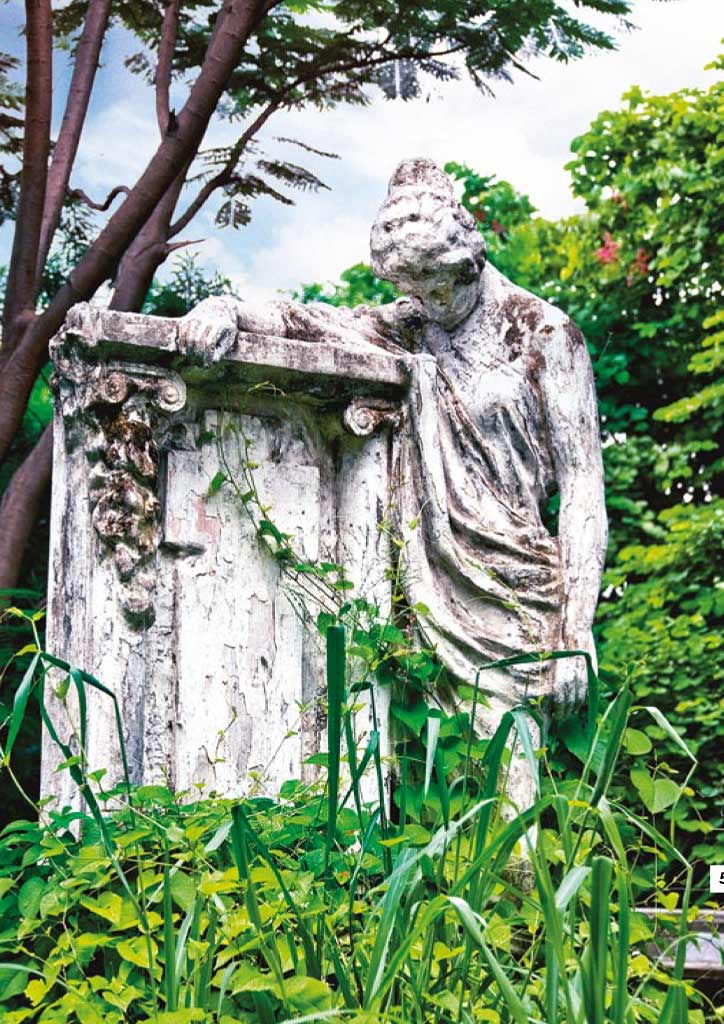

La Loma Cemetery was built at the height of the rural or garden cemetery movement in the Western world; it drew upon innovations in burial ground design in England and France. These rural cemeteries were established around elevated sites at the city outskirts. La Loma was the perfect location, three kilometers from Binondo. Planned as serene and spacious grounds where the combination of nature and monuments would be spiritually uplifting, rural cemeteries were enhanced by grading, selective thinning of trees, and massing of plant materials. The cemetery gateway established separation from the world, and a winding drive of gradual ascent slowed progress to a stately pace. Today, La Loma is so densely crowded with memorials that it looks like a statuary garden in places. However, curved roads, pathways, and marble memorials set against vibrant green plants continue to create attractive scenic vistas and points of inspiration.

YOU MIGHT LIKE: LOOK: Historical landmarks featured at the Intramuros virtual Halloween tour

Chinese Cemetery

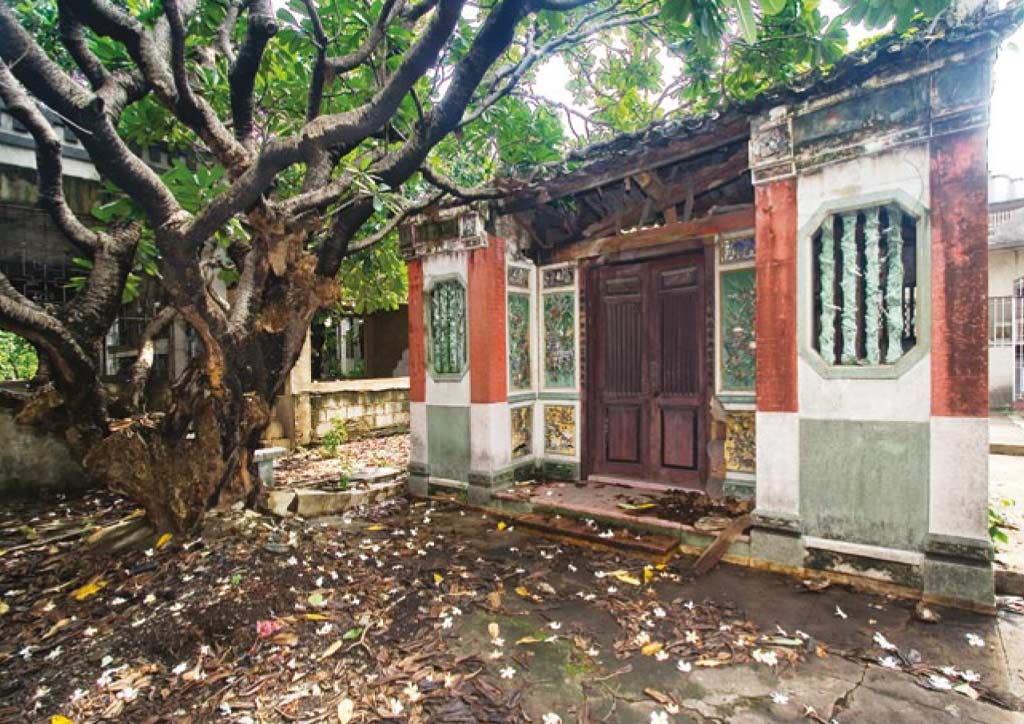

After the opening of the Binondo Catholic Cemetery, the Chinese community of Binondo wanted its own cemetery. The Chinese Cemetery in La Loma traces its history to a candidate for mayor of Binondo who, after winning the election, fulfilled his promise to buy a parcel of land in La Loma. The cemetery was expanded in 1878 and a Chinese-styled Catholic chapel, known as the Chong Hock Tong, was built at this time.

The Chinese Cemetery Catholic Chapel is strikingly Chinese. In its original form, the Catholic indicators of this building were crosses on top of the two bell towers and the main building. The present chapel is now more Chinese in character, and the crosses that adorned the roof and the belfries are gone.

The Chinese Cemetery was also built during the rural cemetery movement and evidence of this original intent can be seen in more hidden, older parts of the cemetery. Today, however, Chinese Cemetery is strikingly urban compared to its neighbor, La Loma. Tight rows of mausoleums hug the main streets and create city-like streetscapes.

Present State

Chinese and La Loma Cemeteries have been active burial grounds since they were founded. The result is a myriad of forms, heights and materials, depicting the various historical and artistic trends of the eras as well as a depiction of the socioeconomic position of Manila’s families. The result is unique: combining ancient (pre-1900) and historic (pre-1960) along with modern and contemporary architectural styles. Variety is essential to the overall character of these spaces. While these are spiritual spaces, there is no shortage of ‘aha’ moments upon turning a corner or simply taking a closer look.

After more than 100 years of continuous use, Chinese and La Loma Cemeteries are a connection to the rich cultural past of Manila. With structures dating back to the mid-19th century, they are a landmark for residents of the city and country alike.

Cemeteries are not merely burial spaces, shown by Filipinos’ continued passion for celebrating All Saints Day with their deceased and living relatives. Established in large part for the benefit of the living, cemeteries perpetuate the memories of the deceased for the living. However, it is a delicate balance—honoring the history of a place but also having a space that breathes and moves forward to accommodate both the needs of the living and the dead.

Many historic cemeteries around the world are being preserved by religious groups, civic organizations and local governments. They are used as teaching tools, tourist attractions and historic destinations. They have proved that there are ways to preserve the cultural heritage and history of a cemetery while retaining the possibility for income generating sales and rentals.

This cultural heritage is an important part of the cultural memory and history of a people and it is important that the public be able to read and explore that record. These cemeteries are spaces that have centered the lives of Filipinos for generations; it would be a cultural tragedy to lose the physical history of these places.

Sources: International Handbook of Historical Archaeology. Theresita Majewski, David Gaimster.

READ MORE: Saving Grace: How Caysasay Shrine, the first stone church, withstood the test of time and disasters