Streetlight Tagpuro – The Winning Presentation

Berlin, 17 November 2017 – When the two teammates met up in Berlin to present their shortlisted project at the World Architecture Festival, Alexander Eriksson Furunes was flying in from Vietnam where he is now based, and Sudarshan Khadka from Nepal, where he had been visiting family.

Their project, an orphanage and community center in Tagpuro, Tacloban, for client NGO Streetlight, was shortlisted in two categories: Civic and Community Completed Building and Small Project. They had a wonderful story to tell of how a displaced people still suffering from the trauma of losing their homes and loved ones to Super Typhoon Haiyan (Yolanda, as most Filipinos call it) came together, opened up about their values and aspirations, and collaborated every step of the way with their benefactor and a team of volunteers to design and build back—better than before—the orphanage and community center they had lost.

How to sell the project to the panel of judges? How to tell the story without trying too hard? It is a humble structure, after all. Sudar Khadka said: “Even when we were making the boards (for submission to WAF), we said it had to be about two things—the process and the project. We know that ideally, a building is both an action and an object. So we knew we had to take care to present both sides of the story.”

Their instincts were affirmed when the firm Leandro V. Locsin Partners presented the project in a “technical rehearsal” and send-off party BluPrint and GROHE hosted for the four Filipino teams shortlisted at the WAF. In a test-run for the WAF crits, the four finalist teams each presented their entries within the ten-minute time limit and engaged in an eight-minute Q&A session with the audience acting as the panel of WAF jurors.

Unfortunately, neither Furunes nor Khadka were able to attend the test run. Furunes was working on a rammed earth project he and Khadka are collaborating on with villagers outside of Ho Chi Minh City, and Khadka was at a welcome reception for the Filipino architects, designers, and artists who had worked on Muhon, the Philippine Pavilion at last year’s Venice Biennale. But a colleague from Locsin Partners presented the material they had submitted to the WAF and answered questions from the mock panel of WAF judges. Streetlight Tagpuro was the first project to be presented, and at the close of the first mock crit, one of the architects, Leandro Poco (yes, he is named after the National Artist) deviated from the format and offered advice to the presenter from Locsin. His advice inspired the audience of architects to ask more challenging questions and give feedback on all the presentations, in the spirit of wanting their compatriots to do their best in Berlin.

The feedback clearly had made its way (and Poco on his own initiative reached out) to Furunes and Khadka who holed up at their hotel for two days revising and refining their presentation. While they could not change the slides (all submissions to the WAF such as drawings, renders, and plans are final and may not be altered), they could work on what they would say. The goal of the re-write was to make their points clear and logical, to include the necessary information to substantiate these points, and above all to tell their story in a manner that would do justice to their design collaborators—the families and children of Streetlight Tagpuro.

The two have generously agreed to share the revised script of their crit presentation, which one of the judges of the Civic and Community category characterized as “very dense and powerful.” Furunes read the first half of the script introducing the project, the challenges, and the design process, and Sudar tackled the second half, on design, construction, and the conclusion.

Watch Furunes and Khadka’s presentation during the live crits for WAF 2017’s Building of the Year by moving the cursor to the -1:59:33 point in the video below.

Introduction

Over the past few years, there has been an increase in the intensity of natural and man-made disasters around the globe. We believe it is important to understand how architects, and architecture, can contribute to post-disaster reconstruction efforts. While there is an argument that architects are the last people needed in this scenario, we have found that the process of planning, designing, and building has the potential to form more resilient communities. By resilience, we mean the capacity to organize and have agency.

The context

About eight years ago, we were invited to Tacloban City in the Philippines to design and build a study center for Streetlight, an NGO providing health and educational support for children of informal settlers and shelter for those living on the street.

The design process

We worked closely with the children and their parents in the design and build of the study center. They later described this process using the Filipino term ‘bayanihan.’ Bayanihan is a tradition where a group of people comes together to achieve a common goal.

The old study center

To the community, the study center was not just a building. It was a symbol of the relationships built in the process and the efforts the parents had made for their children. To put it in the words of one of the fathers: “For the first time in my life, I feel like I have done something great for my children.”

The typhoon

(At this point, they play a 15-second video.)

But on the 8th of November 2013, super-typhoon Haiyan, one of the strongest typhoons to ever hit land, destroyed more than four million households and claimed thousands of lives. The staff and children of Streetlight survived by climbing onto a nearby roof. From here they could see the waves caused by the typhoon flattening the informal settlement and the study center itself.

The relocation

After the disaster, the city government decided to relocate the coastal settlements 16 kilometers north to Tagpuro. Due to the urgency of the situation, the communities were not given a voice in the decisions that directly affected them. People lost their sense of belonging and struggled to fit in the new site they were placed. As shown here, the site of the new Streetlight is located near the main relocation zone in Tagpuro.

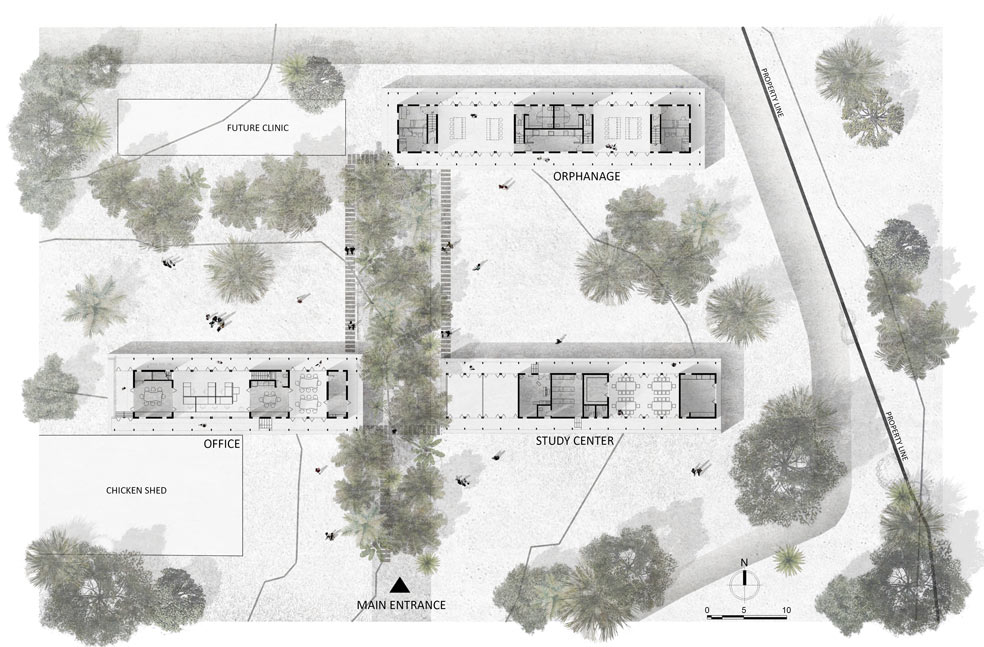

The site and brief

The new site was an opportunity to involve the community in deciding what was needed. We used the existing alignment of trees as the primary circulation axis and divided the site between private and public zones:

- The private zone; consisting of an orphanage, playground, and study center;

- and the public, consisting of a sports ground, office, and a vocational training center for the community.

The decision to place the buildings along the east-west axis minimized heat gain and also benefited from the shade created by the existing trees on site.

The design process

What we learned from the concept of bayanihan is that our role as architects is to provide a framework for collaboration. More than 100 workshops were organized to program, conceptualize, and design the new buildings. Through drawings, models, and full-scale mock-ups, the community developed a common language to express and negotiate ideas and solutions that mattered to them.

The design concept

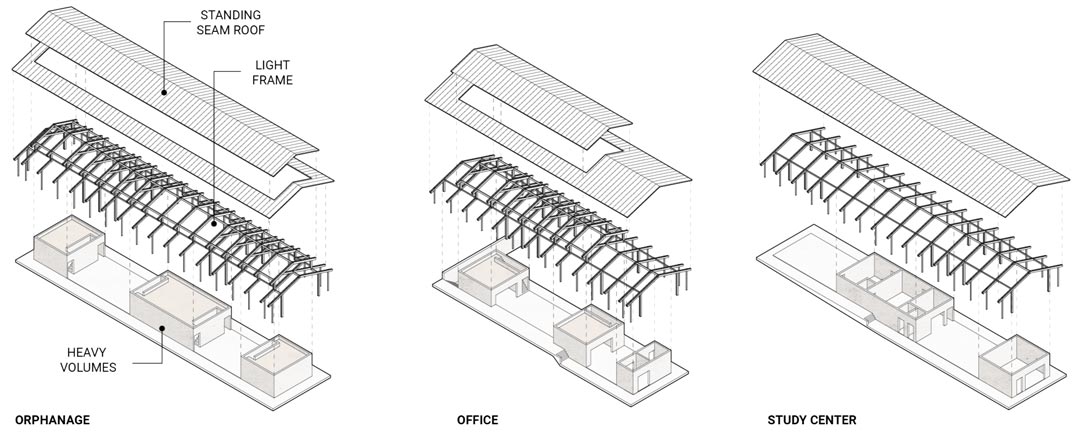

Having experienced the brutal power of the winds and waves caused by the typhoon, the two concepts of ‘open and light’ and ‘closed and safe’ surfaced as the most important to the group. The heavy concrete volumes were designed to provide refuge during typhoons, while the ventilated light timber structures provide for natural ventilation that also allow strong winds to pass through, instead of push, the buildings.

The doors and window details

Once we determined the activities, qualities, and sequencing of each space, we focused on the design of the detailed building elements.

We had a series of workshops, which focused on understanding the doors and windows. The children had made drawings and poems to show what a window and a door meant to them. They described how they used windows as a place to look out at the stars or even as a place where they would serenade the girls that they liked.

The fathers used these poems and drawings as a reference to find windows within their neighborhood that captured these ideas. They documented what they found and presented these back to each other. They then made new designs and created mockups of various materials.

The construction

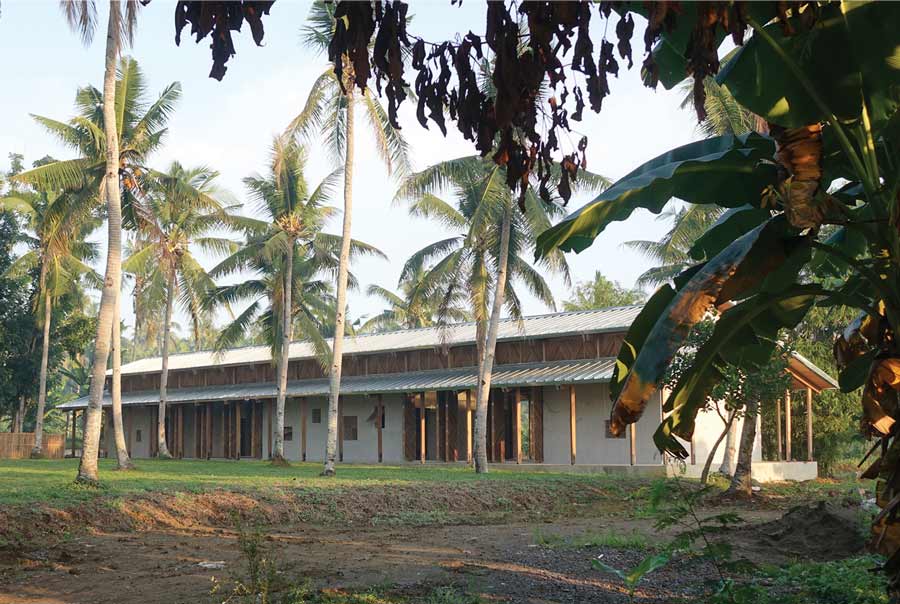

The construction methods selected were deliberately simple for the local community to gain ownership of the entire project from design to construction and beyond. The architecture explores the values of honest materiality, craftsmanship, expressive tectonics, and vernacular sensitivity.

For example, the timber used in building the structural frames was milled from the trees uprooted by super-typhoon Haiyan.

The use of concrete is common locally, so we decided to use it extensively in its raw form. Its surface was manually honed with a grinder to expose the natural texture of the aggregate. In a sense, we found that this lends the warmth of the human touch to the concrete finish.

Lastly, several of the family members were employed on the construction site to do full-scale testing and to work on the buildings eventually. This helped us form a better understanding of the space and served as an opportunity to train those who were employed on the construction site.

The orphanage

When all put together, the various elements of the building form a cohesive framework that the community can inhabit.

This is the main living room of the orphanage. You can see the loft space above for the bedrooms and the service spaces located inside the concrete blocks on the ground floor.

The large screened doors and windows can be opened to form a naturally ventilated recreational space.

The office

The office consists of three heavy volumes containing meeting rooms and utility spaces. The shared workspaces are located in the open areas in between. At times, this building also functions as a vocational training center.

The study center

The study center has teachers’ offices, a music room, library, kitchen, and bathrooms in the heavy volumes; and it has classrooms with areas for song, dance, and theatre in the spaces in between. As such, the new study center serves as the public face of Streetlight and is the space that connects them with the larger community of Tagpuro.

The park

The internal garden is enclosed by the buildings and trees around the site. This serves as a safe space for the children to play and be themselves. Streetlight is able to use the garden for private events such as the graduation of students from their program or, in this case, the opening of Streetlight itself.

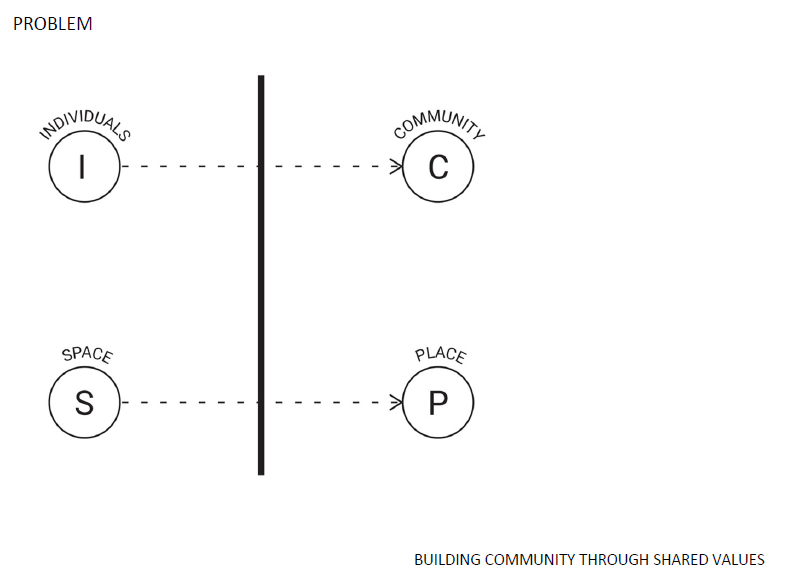

The conclusion

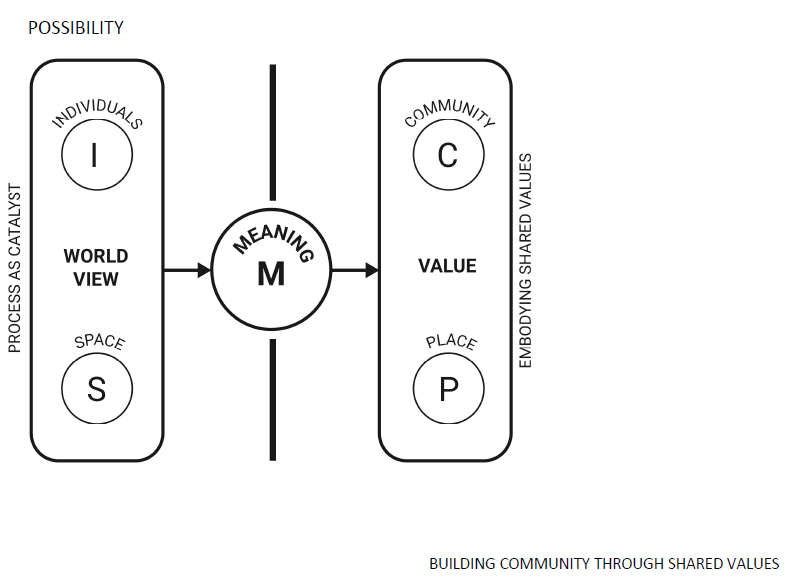

We realized through the whole process that there are both tangible and intangible barriers that prevent the natural transformation of individuals into a community and of space into place. The goal of our collaboration then is to use the design process as a catalyst to form shared meanings, which allow the formation of a community with shared values.

It took three years and a hundred workshops to plan, design, and build back beyond what was lost. We aimed to create architecture that embodies the values of authenticity and sensitivity to context. At the same time, we tried to represent a community’s shared meanings through the design of architectural elements.

Ultimately, we have found that the essence of architecture is not space, but meaning–the meaning that is embodied by space.

For space exists intrinsically, yet it only becomes architecture when given meaning. ![]()